Won could hear the thunder

of the descending rockets as she took the turning to the Kim Il Sung Spaceport,

the noise coming as a vibration that she felt through her hands on the wheel

and the pedals under her feet. The forward view screen didn’t show the glow

from the exhaust yet, just the eternal ochre murk, which seemed even darker

today than usual.

Won let out a breath she hadn’t realised she’d been holding.

She wasn’t too late, then. The arrangements had taken up a lot of time, and

she’d been delayed further by the bottleneck of traffic from what was

euphemistically called Highway Number One, and the clock in the car said she

was twenty minutes after the rocket should have landed. But she wasn’t too

late. The rocket was late, too.

There was nothing new about that. The rockets were almost

always late, due to the weather conditions, and the crew searching for the

easiest path through the sulphuric acid clouds.

She could see the Spaceport now, the low dome of the main

building, the others clustered around it like chickens huddling around their

mother. The only lights were around the huge statue of the Eternal President,

shining up from around his feet, illuminating him as he waved upwards at the

sky. Won had heard that the rockets oriented themselves for landing by using

the statue of the Eternal President as a reference point, and the thought

always made her giggle inwardly. Fancy a statue of yourself, made of the most

indestructible alloy in the history of the human race, put up at enormous cost

and one of the tallest structures on the planet, being turned into a signpost.

The outer airlock gate of the Spaceport’s main entrance slid

open as the sensors registered her vehicle and its identification code. She

drove down the ramp and waited for the airlock to finish cycling the air and

getting rid of the excess heat, a process which took several minutes. The

airlock was decorated with murals of heroic workers and soldiers, green fields,

blue skies, and white-tipped mountains in the distance.

Won had never seen a green field, a blue sky, or a

white-tipped mountain. She’d never known anything other than ochre murk, heat

that would incinerate flesh in an instant, and poisonous air so thick that one

needed to wear a motorised suit of refrigerated armour if one intended to go

outside.

Won was one of the few people who regularly went outside. It

was part of her job.

As the inner airlock opened and she drove into the parking

place, the green light on her dashboard blinked. The car was letting her know

it was safe to get out as she was. Still, she checked the parameters before

opening the door. Electronics had been known to malfunction, and there was

always a first time for airlock doors to fail, too.

She just caught the last of the noise of the rocket as she

came out of the parking area. A uniformed security guard – a human, not one of

the robots which were increasingly taking over that kind of duty – eyed her

doubtfully.

She showed her pass and identity papers. “I’m here for a

passenger from the ship that’s just landed.”

The guard looked, if possible, even more doubtful. “But it’s

a cargo freighter. There are no passenger liners today.”

“I know.” Won glanced at the clock on the wall pointedly.

The smiling face of the Brilliant Marshal smiled benevolently down from behind

the blinking numbers. “There are a few passengers, though, and I’m meeting one

of them. You can call the port manager’s office and check.”

Heaven alone knew how much time that might take, she

thought, watching the guard’s brow furrow in unaccustomed thought. He was like

a machine, programmed to work only one way. No wonder the robots were taking

over his job; there was no difference between them.

“I suppose you’re right,” the guard decided, and handed the

papers back. “It’s landed in Dock Five. To the right, and third turn to the

left.”

“I know where it is.” Won favoured him with a plastic smile

and walked away. The spaceport’s hall was pleasantly cool, and pale green light

sprinkled down from high above, shining through a series of spinning mirrors so

that the faint shadows constantly fractured and shifted. It was fascinating to

first time visitors, but Won was long since inured to the effect.

The ship would still be in the long and complicated process

of docking, so she stopped at one of the shops, run by a woman she knew. “Hi.”

“Byong-Uk!” the woman, Ri, grinned. “You’re the first good

thing I’ve seen here today.”

“That bad, is it?” Won waved at the empty hall. “Nobody

buying stuff?”

“Who’s there to buy? No passenger ships means no passengers,

and no passengers means nobody buying anything. That’s why I brought a novel to

work. Have you eaten?”

“Yes,” Won lied. She hadn’t, since breakfast, but the shop’s

food looked like wax and plastic in the hall’s shifting light. “Thanks, anyway.

How’s the family?”

“Fine. The younger kid just started school. Shouldn’t you be

getting married by now?”

“Ah...you know me. Not the marrying kind. I’d make any man

miserable, and nobody deserves that. Is your husband still working there in the

immigration section?”

“Yes. Are you meeting someone? Do you need any problems

smoothed out?”

“I shouldn’t think so. I’m picking up a guest, but this is

an impeccably official one.” Won’s mouth struggled to shape the unfamiliar

syllables. “Professor Usha...Bhattacharya.”

“Sounds Indian.”

“Yes, she’s from Delhi University. Apparently she asked for

me as guide, personally.”

“Really?” Ri grinned. “You’re getting famous.”

“Famous? No, it just worries me that anyone would want me in

person. Puts more of a responsibility on me, you know? If something happens,

it’ll be my fault.”

“You worry too much.” Ri cocked her head as an announcement

sounded, tinny over the public address system. They’d managed to set up this

station, she’d said to Won once, but they hadn’t managed to make a loudspeaker

that one could understand without trouble. “I think they’re done docking now.

You’d better get going.”

“You’re probably right.”

*********************************************

Professor Usha

Bhattacharya was half a head taller than Won and thin to the point of

emaciation. When she grinned, her skin stretched over her bones like dark leather

over a skull.

She was friendly enough though. “Won Byong-Uk? You’re much

younger than I thought, and much prettier, too. Your photos don’t do you

justice.”

Won smiled politely, and switched her thoughts from Korean

to English. She always found it easier to speak English when she thought in the

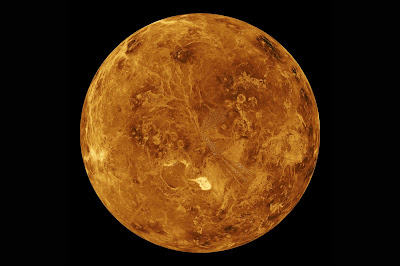

language. “Ma’am. Welcome to Venus.”

“It isn’t like what I thought it would be.” Bhattacharya

peered at the image on the screen as Won drove the vehicle out on to Highway

Number One. “I’ve seen the photographs and the videos, of course, but they

don’t really show it as it is. I didn’t, for example, know that everything shimmers.”

Won set the autopilot.

“Is this your first time outside Earth, Ma’am?”

“I’ve been on the Moon, and I was offered a position on Mars,

but...” The tall thin woman shrugged. “I was always happier at home, anyway.

But here I am, right?”

“Yes, Ma’am.” Won noted without comment the distant glowing

lights of the work camp far to the right, where the new satellite town was

being blasted out of the bedrock. There was no reason to point it out to Earth

visitors, who would undoubtedly fail to understand why, though most of the work

was done by robots, human prisoners were at work down in the tunnels as well.

“How long do you intend to stay, Ma’am? I haven’t been informed about the

duration of your visa.”

“Well, that depends.”

Bhattacharya’s long thin fingers drummed on the arm of her seat. Won found the

motion fascinating, like the movements of a scorpion’s legs. “I’m here on

research, you know, not as a tourist.”

“Yes, Ma’am, I’ve been told that. But I haven’t been told

what you’re researching.”

“The ruins found along the Baltis Vallis,” Bhattacharya

answered at once. “I am an archaeologist, so naturally that’s what I’m

researching.”

“Ma’am...” Won tried to find the words. “I’m afraid that

there’s no proof that they ever were ruins of any kind. The consensus, as I’m

sure you know, is that they were just shaped by erosion and temperature.”

“Yes, well, I’m here to make my own mind up about that.”

Professor Bhattacharya grinned again. “And as you know, I asked for you, specifically, as my guide. Do you

know why?”

Won felt her heart sink. “Because I’ve been to Baltis...”

“Yes, because you’re one of the few guides familiar with

that part of the planet. Don’t worry, I’m sure you’ll do very well. Is that the

city up ahead?”

“Yes, that is Chikhalsi Geumseong. It means Capital City of

the Star of Gold. It’s almost all underground, of course. The structures above

ground are mostly for heat management.”

“Yes. That must be a problem. I remember Venus is called the

Star of Gold in your language.” They were close enough now that the great heat

dissipating fins could be seen glowing in the ochre murk. “Do you ever have

breakdowns?”

Won wondered briefly if she was permitted to answer this

question, and decided it wouldn’t do any harm. After all, nobody could deny

what the conditions on the planet were like. “Frequently, but each system has

multiple backups. It’s the corrosion that does the damage.”

“Um, yes.” The next question was a surprise. “Do you have a

family? Your biography doesn’t say.”

“My parents live in Yeubeong, down in the southern

hemisphere.” Won took over from the autopilot and steered down the ramp of the

nearest airlock. “I have my own rooms here, in a dormitory.”

“Do you miss them?”

Won thought about the possible responses, and went for the

honest one. “Not much. My parents can be difficult.”

“All parents can.” Bhattacharya glanced at Won. “You’ve

never been off Venus, have you? You were born here.”

“That’s right, Ma’am.” Won was uneasy, with all these

personal questions, but she had to keep the woman happy. “We’re on Kim Il Sung

Avenue now.”

It was just a broad flat tunnel carved arrow-straight

through the rock, the rock surface overhead deliberately left unfinished except

where it was set with the broad flat panels of the lighting system. Policewomen

in stubby towers at regular intervals watched the traffic and the sensors. Won

turned into a side tunnel opposite to one of the towers. “This is the way to

your hotel, Ma’am.” The University had offered the visitor accommodation, but

Won had been informed she’d chosen to have arrangements made at a hotel. “A hotel” meant, of “the hotel,” because there was only one approved for off-planet

visitors. “You did wish to stay in a

hotel, not at the University?”

“That’s right. I’d rather not be bogged down too much by

interaction with fellow academics. Their opinions might...influence my

thinking, and I don’t want that.”

Won thought about the Party representative whose only

purpose was to influence everyone’s

thinking, and found herself smiling. “I understand, Ma’am.”

“Good, so we understand each other. How soon can we arrange

a trip to the Baltis Vallis?”

Won was surprised. “It depends on your schedule, Ma’am. Your

research programmes and meetings...”

“I have no other important research programmes and meetings.

Those I have will wait. How soon can we do it?”

The Heavenly Gold Star Hotel hugged two-thirds of a circular

cavern with glass-smooth walls, carved out by the first explorers, long ago.

There was a statue of Kim Jong Il in the middle of the cavern, but only a small

one, used as the centrepoint of a roundabout. Won turned past it and eased the

vehicle to a stop beside the hotel’s main door while considering the answer.

“Tomorrow morning standard time, nine hundred. Will that be

all right, Ma’am?”

“Excellent. What will I need to bring?”

“Just whatever equipment you’ll need for your research. It’s

my job to provide the rest.”

“That’s great, dear. You’re being very helpful.”

“It’s just my duty, Ma’am.” Won smiled tightly, but her mind

was already whirling, thinking of arrangements and requests for permission.

There were eighteen hours left, and she’d need every minute of that. She’d get

no sleep tonight.

Well, it wouldn’t be for the first time, she thought, and led

the Professor into the hotel, to help her check in.

**********************************************

They’d been crawling over

the eroded plain for so long that even Professor Bhattacharya had grown weary

of looking out at the landscape.

The crawler was big. It was bigger than they’d needed or Won

had actually wanted, being actually a ten seater meant for a larger expedition;

but it was the best she’d been able to get her hands on at short notice. It was

slower than the smaller models, and had a shorter range because of the drain on

the batteries. On the other side, it was roomy and they could move around

enough not to get on each other’s nerves.

The Professor didn’t seem to mind being confined in what

amounted to a large metal box on caterpillar tracks. After she’d grown tired of

looking at the view screens, she’d unfolded a computer from a tube scroll, one

of the latest and most expensive models, and worked on it for a while. Then,

all of a sudden, she’d raised her head.

“Do you ever wonder if we’re jealous?”

Won had been keeping a careful eye on the temperature

gauges, always the most important thing on a Venus surface crawler, and was

startled at the question. “Ma’am? Who are you asking about?”

“We, you know, all the other countries in the world.”

Professor Bhattacharya sipped water from a bulb connected to a hose. The bulb

delivered only a predetermined amount of water per sip, so that nobody – driven

to psychological thirst from awareness of the intense heat outside – could

drink the water supply away in a few hours. It had been known to happen. “Do

you here, on Venus, ever wonder if we’re jealous of you?”

Won blinked at the thought. “No, ma’am. Why should we be?”

“I mean, you have a right to wonder. It would be natural for

us to be.” The older woman rolled up her computer and pushed it back into its

tube. “Everyone had imagined Venus could never be colonised, at least not

unless and until it was terraformed in the far future. It was simply, they

said, too hot and too corrosive, and not worth having. So they concentrated on

squabbling over the Moon and Mars and even Mercury – you know the Chinese have

claimed the planet as their sovereign territory – and then, and then, your

country just went ahead and took over Venus. So it would only be natural if you

wondered if we were jealous.”

“How would it matter, Ma’am? Nobody else has plans to invade

Venus, right?”

“No, and they don’t really think it’s worth it in any case.”

Bhattacharya watched as a low ridge grew on the forward screen. “But we know

better, don’t we?”

“It’s not really worth anything to anyone except us, Ma’am.

And to us it’s just home.” Won put her hand on the controls in case the crawler

needed assistance to climb the ridge, but the autopilot managed, albeit with

groans from the engine. “Why do you ask?”

“It was just a thought.” Professor Bhattacharya seemed

mildly disappointed that the terrain beyond the ridge was just more of the

ochre plain. “Your country pulled off an amazing feat, you know. Just managing to reach this planet in total

secrecy was amazing enough, but the engineering that allowed it to take Venus

over...well, you know as well as I do what a great achievement that was.”

“Yes, thank you, Ma’am. I am a descendant of one of the

members of the first expedition, as you may be aware.”

“I know. Your biography mentions it.” Won felt the Indian

woman’s intensely curious gaze. “So, what is it like?”

“Ma’am?”

“Living here, all the time, behind closed airlocks and

temperature shields. Knowing you’ll die if you’re exposed to the environment

even for a millisecond. Hell, even on Mars...even on the Moon...conditions are much less hostile than this.” She gestured at

the ceiling. “Neither of them has sulphuric acid rain falling continuously, but

evaporating before it hits the surface because it’s so damned hot. How do you

feel about it?”

Won shrugged, keeping her eyes on the temperature readings.

One of the radiators on the crawler’s roof seemed hotter than it should be, and

she adjusted its position with a touch of her finger on the screen. “How should

I feel about it? It’s all I’ve ever known.”

“Yes, but when you go outside, you’re in a suit that makes

even a spacesuit, let alone a Martian pressure suit, feel like...like nudity. Don’t you ever imagine what it

might be like to run barefoot along a beach under a cloudless sky, the sun in

your face and the wind in your hair, next to a bright blue sea?”

Won swallowed. “I don’t know what you’re getting at, Ma’am.

These questions might be appropriate to my great grandfather from the first

expedition. They’re meaningless to me.”

“Sorry. I didn’t mean to upset you.” Bhattacharya began to

unroll her computer, and then paused. “You know, even back on Earth, I heard

good things about you.”

“You did, Ma’am? Who said anything about me?”

“People. People you guided, and others too. I won’t take

names, but you can believe me that you were exactly what I was looking for – the

perfect guide. That’s one of the three reasons I asked for you.”

“Thank you, Ma’am, but I’m nothing special.” Won remembered

that the second reason would be that she was familiar with the surface. What

was the third? “Anyone else trained in surface travel could have done the job

equally well.”

“Is that so?”The professor smiled her death’s head smile.

“We’ll see.” She sucked at the bulb again. “Just that light makes me thirsty,”

she said.

Won smiled politely and suddenly felt very thirsty herself,

indeed.

“The light does do things like that, Ma’am,” she said.

**********************************************

“We’re almost there now,”

Won announced.

“Where?” Bhattacharya peered at the screen. “I can’t see the

Balitis Vallis.”

“The Vallis is further on, Ma’am, beyond that line of low

ridges there. It’s very broad and shallow at this point, so you wouldn’t be

able to see much of it even if we got right to the edge.”

“Pity. The largest channel in the Solar System, isn’t it? I

wanted to see it for myself.”

“We can follow it further north until it deepens, Ma’am.

Even then, the light and atmospheric conditions mean you won’t be able to make

out much. Still, it is more impressive there. But this is the location you’re

interested in.”

Bhattacharya drew her breath in sharply. “Are the ruins here?”

“The ruins, as you call them, are scattered on this side of

the Baltis Vallis. I’m afraid that you’ll probably be disappointed. They’re

badly eroded and you can’t really tell what shape they ever were supposed to

be, even if they were ruins in the

first place.”

“I’ve seen the pictures. What do you know about them?”

“I, Ma’am? You mean, what I know personally? Not much more

than the average person. Park Kyung-Lim found them first, on the first ground

exploration of the Baltis Vallis, soon after the first landing. At that time

they didn’t have suits – even their ground exploration vehicles were very

limited compared to this crawler – so he couldn’t examine them closely. He

didn’t call them ruins, though. He just said they looked as though they might

have been ruins once.”

“I know what he said. And I’ve seen the photographs he took.

They looked very suggestive, don’t you think?”

“Afterwards, when exploration parties on the ground went to

look, they didn’t find anything so clear,” Won pointed out.

“Maybe they weren’t looking in the right place, or maybe

they didn’t want to find ruins. After all, if ruins were acknowledged to exist

on Venus, it would pose a fairly

colossal problem for scientists, don’t you think? Venus, which everyone agrees

never had life and which has been a poisonous furnace for thousands of millions

of years...has ruins? How could

anyone, from astronomers to biologists, explain that?”

“Perhaps,” Won acknowledged. “But, Ma’am, isn’t science

always self-questioning, looking for new facts and adjusting itself to...”

“Science, yes. Scientists,

no.” Bhattacharya snorted. “Once you’ve had a taste of faculty politics at any

university, you’ll find out scientists are twice as opinionated and petty as

your usual office bureaucrat.”

“If you say so, Ma’am,” Won replied politely. “It’s your

field, after all, not mine.”

“Uh-huh. Your impressions and opinions are as important as

anyone else’s. More important, in fact, since you actually have visited them

yourself, unlike well over ninety-nine percent of the so-called experts. What

did you think of them?”

“What did I...” Won frowned, thinking. “Well, the first time

I came out here, I was still a trainee, and working hard simply to make sure I

didn’t make any stupid mistake. I didn’t

even get a proper look at the place. The second time, well, I wasn’t actually

going to them. I was accompanying a team setting up instruments in the

Baltis...”

“Instruments?”

“Meteorological observation instruments, Ma’am. The channel

has its own weather system, with the low winds blowing north to south along

it.”

“Oh yes. And then?”

“So it was only the third time I was out here that I really

saw them.” She shrugged. “At the time they didn’t seem to be all that special

to me, to tell the truth. I suppose I was simply not knowledgeable enough to be

impressed. And after that...” she fell silent.

“After that?”

“I’m sorry, Ma’am, I think my impressions will simply not be

of much use to you.”

Bhattacharya didn’t seem perturbed. “Well, there’s always

this time. Try and remember what you think when we get there. Let’s see how my

impressions match up with yours.”

Won reached for the controls. “We’ll have to stop soon and

use the robot cameras.”

“Can we go out to them?”

“Do you really want to, Ma’am? We’ve got robot cameras and radars

that can give you better views from here, without the risks of an

extra-vehicular...”

“No!” Bhattacharya snapped. “I need to see for myself.”

Won nodded and took over from the autopilot, slowing the

crawler down and coasting to a stop. “Very well, Ma’am. I’ll prepare the suits.

Do you have any idea how to use them?”

“No, but I’ve used a spacesuit on the Moon, and...”

“Ma’am,” Won interrupted, “we aren’t on Luna here, and the outfits

we’ll be using – they aren’t like spacesuits at all. Come along, I’ll show

you.”

The “suits” were motorised cylinders twice as tall as a big

man, with remote-controlled arms and a tripod of legs that ended in three-pronged

claws that could cut into the surface if necessary, or spread themselves out to

spread the weight. The cylinders were studded with short tubes ending in hooded

lenses, and atop each of the two of them was something resembling a folded

silvery concertina. Won explained that when outside the crawler, these would

open and spread out into a fan shape, radiating heat.

“If they fail,” she continued, pointing to a box resembling

a backpack attached to one side of the cylinder, “there’s this emergency

auxiliary unit, but it can only work for half an hour or so. It’s basically so

that you can get back to the crawler as quickly as possible.”

“Half an hour? What if you’re too far away to...”

“No. One of the rules of surface work on Venus is that

you’re never more than half an hour from an airlock and safety. Not even

the...” Won decided not to say that not even work camp prisoners were exempt

from this rule. “Not even the most expert,” she amended, “ever allow themselves

to break this rule. It would be suicidal.”

“I see.” Bhattacharya walked slowly around one of the two

cylinders. “Do the cooling systems ever fail?”

“Sometimes.” Won felt her throat clutch suddenly, and

swallowed hard. “Not often, fortunately, but it happens.”

Bhattacharya glanced at her and back at the cylinder. “So,”

she said casually, “just how does one get into one of these things?”

**********************************************

Won sat in the suspension

harness of her suit, her hands and feet on the control surfaces that manipulated

the thing’s limbs. It was like walking while sitting on a spring-loaded stool

partly suspended from the ceiling, and took getting used to. Even Won, who’d

logged hundreds of hours in suits, always took time to get used to one. Even

though each movement of the suit was controlled by motors at every joint, it

was slow and sluggish. The atmosphere was so thick that it was like walking

along the bottom of an ocean. In fact, that was exactly what they were walking

along: the bottom of an ocean of carbon dioxide.

“Remember that even a breeze

here is a pressure wave,” she’d reminded Bhattacharya. “I checked the weather,

and we won’t have storms, or we would never have even come out here. But a

strong wind can knock you over.”

“I’ll remember,” Bhattacharya had said, her face twitching

slightly in an inadvertent display of distaste.

“And the temperature,” Won had continued. “There are warning

lights, but keep an eye on the temperature readouts at all times.”

Around her head, the interior wall of the suit was a

wraparound wall of superimposed video images, arranged so that the view from

one camera merged with that of the next, as though the top of the tank was

nothing more substantial than a sheet of glass. If she had wanted to, she could

switch to various enhanced views, or radar vision, but for now she preferred to

stay in the normal vision spectrum. It was all Professor Bhattacharya would be

using; Won had stressed that she was not to use any of the more complex

features of the suit so as not to make a mistake. And so Won had decided to

match the other woman’s experience as closely as possible, relying on her greater

experience and training to spot problems before they occurred.

Ahead and to her left, the suit housing Professor

Bhattacharya was outlined shining silver against the ochre light, the radiator

atop unfurled into a crest as high as the suit itself again. If the cameras

hadn’t been filtered, the suit would have been almost too bright to look upon

with the heat it was radiating, and its outline distorted with the shimmering

of superheated air; but the suit’s computers corrected that to make it bearable

to her eyes. She studied Bhattacharya critically. The older woman lurched

along, in the typical clumsy movement of beginners. However, the professor was

already visibly improving, and was far more stable than when she’d taken her

first few tentative steps around the crawler. Won wondered if she’d had some

simulator training on suits somewhere.

“Professor,” she said into the radio. “Are you doing all

right?”

“Yes, I’m all right. This is...quite fun.”

Won grimaced. “Please be careful and remember exactly what I

told you. Above all, Ma’am, don’t hurry.

We’ve plenty of battery life left, and we can always go back to the crawler for a

recharge.”

“Yes, I get it.” Bhattacharya picked her way through a

cluster of flattened blackish-red rocks partially buried in the ground. Won

watched to make certain she wouldn’t accidentally step on the smooth surfaces

and slip, but she remembered what she’d been told. “How much further are the

nearest ruins?”

Won consulted her suit’s coordinates, though she didn’t

really need to. “A hundred and fifty metres to the north-east, Ma’am. To your

left.” Giving the blackish-red rocks a wide berth, she followed the other suit

towards Park’s discovery.

At first sight they really did look like tumbled walls and

the remnants of staircases. But they would have been walls of buildings made

for giants, and the stairs were so steep and narrow that the feet that might

have trod them could never have belonged to anything remotely human. And that

crumbled, vaguely cylindrical mass of stone...could it once have been a tower,

or a pillar supporting some titanic, long-gone roof? Or, as seemed more likely

the closer one got, it was all just the product of lava flows and erosion.

Professor Bhattacharya seemed to have no such thoughts,

though. Her exclamations of delight sounded in Won’s earphones as she walked

her suit past what seemed to be a wall and to the possible pillar. The young

woman had the feeling that, if the Indian professor could have, she’d be down

on her hands and knees, crawling along the ground and peering at the rocks

through a magnifying glass.

“Look at this!” she exclaimed. “I’m sure this is

artificial!”

Won shrugged mentally. It was pointless to say anything

either in agreement or otherwise. “Ma’am, you need to be careful. Sometimes there

are bubbles in the rock left over from the lava flows, and the stone shell on

top could collapse from the weight of the suit.”

“Oh, fiddlesticks. These are probably older than the lava

flows, and they’d have been buried.” Bhattacharya’s suit extended an arm, the

rotary cutter extending from the tool cluster at the end, already revolving. “I’ll

need to take samples to study.”

“Ma’am...” Won began.

“Don’t worry. I’ve got permission. You can radio and check.”

“I’m certain you have,” Won said. The official conclusion

was that the “ruins” were merely suggestively eroded stones, so that they had

no real value and weren’t protected. “I meant to say, please don’t cut out

pieces bigger than the suit’s external storage bins can handle.”

“Yes, I know.” The cutter disc bit into a slab of stone,

chips rising into the soup-thick air. “I won’t take any more than I need.”

“Yes, Ma’am.” Suddenly Won felt immensely weary. Everything

seemed unreal to her, as though she was watching from very far away, from a

bolt hole at the very back of her head. The ochre land, the gleaming cylinder

of Bhattacharya’s suit, the interior of her own, were all very far away. She

took a deep breath and held it, squeezing her eyes shut, fighting down sudden

waves of memory. It had been like this, everything very far away, as she’d

lain, trapped in her suit, when...

She became aware that someone was calling her by name.

“Byong-Uk?” Professor Bhattacharya’s voice sounded in her earphones,

insistently. “Are you all right? Is anything wrong with your radio?”

Won found that she was shaking. She forced herself to relax.

“No, Ma’am,” she lied. “Everything is all right. I was just checking my suit’s

parameters. Are you done?”

“At this site, yes. Where is the next?”

“A little further north. We’ll have to use the crawler to

get there.”

“That’s good,” Bhattacharya said. “I don’t know about you,

but I need a break from this suit. And I need to study these samples.”

“Fine, Ma’am,” Won said, trying to unclench her fingers and

toes so that she could use the controls. “That’s quite fine.”

****************************************************

Several hours passed before Bhattacharya spoke again.

Won was navigating the

crawler around a fissure in the plain. It wasn’t a particularly deep fissure,

but was just too wide for the crawler to cross directly, and she had turned the

vehicle to follow it until she could find a safe crossing place. She’d welcomed

the diversion; it had distracted her from her thoughts.

She was peering at the

screen, her hand on the control wheel, when Bhattacharya’s voice startled her.

“There was a third reason I chose you to be my guide.”

Won glanced over her shoulder

to where Bhattacharya was crouched over her precious samples, working on her

unrolled computer. “Ma’am?”

“You heard what I said,

Byong-Uk. There was a third reason I asked for you, in person. In fact, this

third reason was so important that if I hadn’t got you I’d have postponed my

trip until you were available.”

Won’s heart began thudding in

her chest so hard that she could feel it. With difficulty, she kept her voice

level. “What’s that, Ma’am?”

“This is a pretty closed off

society you have on Venus,” the Indian woman said, “one that’s led to your

being called a Hermit Planet. I don’t blame you for that – quite the reverse,

in fact – but you do realise that things get through sometimes? Rumours, for

instance?”

“What rumours, Ma’am?”

“Well...” Professor

Bhattacharya looked back to her computer with elaborate unconcern. “I heard

about a young woman who was lost – who was in fact given up for dead – but

returned from the desert, well after she should have run out of power to run

her suit, alive and with a strange tale to tell. I heard that this tale caused

such tremors in the government, so many possible repercussions, that this young

woman was ordered to forget that any such thing had happened, and that the

entire episode was erased from the official record. Have you ever heard this

rumour?”

Won’s mouth seemed to freeze,

unable to answer. The sound of her heart grew louder and louder, until it

filled the universe, and once again she felt herself shrink to a dot of

consciousness at the very back of her skull, peering out through her eyes as

though through long, long tunnels at a scene very far away. And the scene at the

end of those tunnels wasn’t the familiar control panel of the crawler; it was

the edge of the broken rock overhead, and, beyond that, the swirling ochre

clouds of the sulphurous sky.

She’d been careless. Even then, she’d been aware that she

was taking risks. But the prospect of being alone for the first time on the

surface, unsupervised and able to do as she pleased, had filled her mind with

an intoxicating sense of freedom. There was only the crawler behind her, the

nearest base was far away, the other members of her group were setting up a

drilling platform to look for they alone knew what, and she could do what she

wanted.

There had been the melted masses some people called ruins

nearby. They hadn’t been very clearly visible from near the crawler, and she’d

wandered over for a closer look. One, in particular, had interested her

immensely; a narrow, roughly conical spike pointing upwards at the clouds, like

a crooked finger. On another planet it wouldn’t have been remarkable; but on

Venus, where the air itself pressed down with the weight of a sea and almost

five times as hot as boiling water, it should by all rights have eroded away

long ago.

The tip of the rock spike had been hard to see in the dull

ochre light, but she thought that she could make out a mark that looked almost

as though it could be a hieroglyphic. Tilting her cameras back and magnifying

the view hadn’t made it much clearer because of foreshortening, so she had

begun backing away for a longer view. That had been, as she’d found out a

moment later, a mistake.

Many aeons ago, molten lava had roared over this land,

almost as fluid as water. It had pooled in hollows and carved out ways for

itself, and sucked at the bases of cliffs and boulders, seeking hungrily to

undermine them and bear them away. Then, as its ardour cooled, it had grown

sluggish and congealed; but, like an old man still trying to deny the toll of

the years, it had crept on, until it could go no more. And in its slow progress

it had made caps and lids over clefts and fissures in the ground which in its

hotter, younger times it would have filled to the brim and crushed out of

existence.

As the years had passed into decades and centuries, the

soup-thick air had worn away the stone cap, scraping away the lava sheet little

by little until only an eggshell-thin skin of rock remained, ready to collapse under

the slightest weight. And Won’s suit, as she backed away from the spire, was

very much more than the slightest weight.

Won could still remember how it had happened. Each time she

closed her eyes she could see it again, as though in slow motion. Suddenly, the

suit had tilted over backwards so sharply that her helmet had cracked against

the rim of the pilot’s chamber. The cameras, trying to focus on the rock spire,

had jerked upwards dizzyingly, staring up into the ochre sky. Before she could

try to recover balance, the surface beneath her had given way completely, and

she’d felt herself falling. Dust and stone fragments had come down with her,

burying her in a cloud of her own. Over the noise of the crashing stone and her

own screaming, she could hear the noise of ripping metal.

When the cloud had cleared, she had been lying on her back,

looking up. On both sides the rock had risen like walls, until they ended in a

jagged hole through which she could see the clouds.

She’d known instantly that she was in bad trouble. The

ripping noise that she’d heard could have been only one thing –the heat

radiator crest had torn away, and she could even see part of it, gleaming

dully, leaning against the side of the rock. That meant she had only half an

hour to get out of here and back to the crawler – and even if she’d been on the

surface, she’d have been hard pressed to make the vehicle in half an hour. She’d

wandered a fair way.

Trying to lever herself up, she’d realised something else.

Whether the crawler was half an hour or half a minute from the hole above was

immaterial; she couldn’t even get up. The suit was buried under so much rock

debris that she couldn’t move the limbs. It was amazing that all her cameras

hadn’t been covered up as well.

Struggling to control her fear, she’d tried to call for help

on the radio; and it had been no surprise at all to her when all she’d heard

was her own voice, muffled through her helmet. The fall had smashed up so much –

why not some part of the radio as well?

And then she’d realised that she was going to die. She’d lie

there on her back, helpless to move, as the power in the suit gave out. Long

before the air, breathed in and out over and over, became too laden with carbon

dioxide to breathe, she would feel the temperature begin to rise. At first, she

imagined, it would be slow, almost imperceptible, as the coolant system kept

ticking over. But then, as it finally stopped working, the temperature would

begin to rise sharply, from room temperature to that of a broiling summer day

on Earth, and then further, to the point where one couldn’t bear it rising

anymore. But still it would go up, and up, further still. And then it would

cook her alive, inside her own skin.

At that realisation

she’d almost lost her mind for a minute or two. Wriggling frantically inside

the narrow confines of the pilot’s chamber, she’d tried to reach the door,

thinking hazily to open it and get out, to try and reach the crawler on her

own. Dimly, she’d been aware that even if she did manage to get the door open,

she’d burn to a crisp instantly in the furnace outside, long before the carbon

dioxide sea simultaneously crushed her lungs and suffocated her, long before

the sulphuric acid in the air began eating her skin and flesh away. But even

that would be a better death by far than feeling herself cook inside her skin.

It was a hopeless effort. Even with the emergency manual

override, the door, jammed against the rock, had been impossible to shift.

It is a sad thing to know one is going to die, far away from

any help, lost and frightened and alone. Won hadn’t even been able to cry;

finding the door immovable, she’d lain back in her harness helplessly and

stared up at the clouds. By an ironic coincidence, she’d been able to see the

tip of the rock spire poking above the rim of the hole, and from her position

had got a fairly good look at the marking that had caused the whole trouble.

And, inevitably, she’d been able to finally see that it was just an oddly

shaped stain.

She’d begun to fancy that she could feel the first rise of

temperature. It was surely too soon – she couldn’t have been down here for ten minutes

yet, let alone half an hour – and the gauge didn’t show a whit above twenty

degrees Celsius. But she found herself watching it obsessively, waiting for the

inevitable rise of the green line on the black screen, its slow and deadly

change to amber and towards red.

At least she wouldn’t see it reach the deepest red. Long

before then, she’d be a corpse, her blood boiling away inside her veins.

Maybe by now the drilling party would have finished their

work and returned to the crawler. Undoubtedly, they’d be calling to her on the

radio, anxiously looking for her with the crawler’s robot cameras as well as

their own suits. But their radio calls would go unanswered, the cameras would

show nothing, and she could be anywhere within a half-hour’s travel radius.

They’d be frantic, but they wouldn’t find her except by the purest accident.

And even if they did, it would be too late.

She’d been watching the gauge so intently that at first she

didn’t notice the noise. Even if she’d noticed it, she mightn’t have thought

about it twice, imagining it was just the collapsed stone and dirt around the

suit, settling. But it wasn’t.

When the grinding scraping sounded along the side of the

suit, her head snapped up, an involuntary cry coming from her mouth. The noise

had come, not from above, but from below and to the side. Something under the suit was grinding and scraping at it. Even as

she listened, holding her breath, it had come again.

Something dark had appeared on the edge of one of the

cameras that was still working. At first it had moved slowly, a black line at

the edge of the screen, expanding to a band and then a curved blot that moved

slowly over the viewing surface. It had paused, seeming to hesitate, and then

covered the screen completely. Then the suit had jerked suddenly, even as the

scraping noise began again.

Slowly, like a

falling tree in reverse, the suit had begun to straighten. The rock above and

around it had heaved up like water in a swimming pool around the shoulders of a

swimmer, and fallen away. It had straightened in lurches at first, as though

whatever was pushing at it had to rest to draw breath between efforts. Then, as

most of the rock had fallen away and she’d been able to lever with some of the

power of the suit’s limbs, it had moved more smoothly. And then she was

upright, and something below her had been pushing her up the wall of rock,

towards the surface.

Some things. From

the peripheral view of the few cameras she’d still had functioning, she caught

a glimpse of movement on all sides of the suit. Whatever it was that was

pushing her up, there were many of them, and they were working as a team.

She’d only caught a brief glimpse of them, just before she’d

managed to use the suit’s arms to drag herself the last bit of the way to the

surface. Then she was on top, and the temperature was now quite definitely rising, and she still was far

away from the crawler and safety. But at least she’d finally had a chance.

She hadn’t lost that chance, though it’d been a near thing.

If the drillers hadn’t been out looking for her, and if one of them hadn’t

spotted her and they hadn’t managed to get to her in time, it would’ve been too

late. Even then, it had been weeks before her body had repaired itself from the

ordeal.

Her mind? She’d long

since realised that it never would. And this woman had just scraped away the

thin scab she’d grown, and the wound was there, as red and raw as though it had

been made yesterday.

“Did you ever hear this rumour, Byong-Uk?” Professor

Bhattacharya repeated.

Won felt her mouth twitch, her tongue moving. “I...don’t

know what you’re talking about, Ma’am.”

“Of course you do, and let’s not play games.” Bhattacharya’s

voice was hard as one of the rock samples on the table. “You had an accident,

which you shouldn’t have been able to survive – which you literally had no way to survive – but you did. And

whatever it was that helped you to survive, it was something that scared the hell out of your authorities – to the

extent that they erased the whole episode from the record. To all intents and

purposes, it might as well never have happened. What do you think that might

mean?”

Won said nothing.

“I’ll tell you what I

think,” Bhattacharya went on. “What I think is that you were helped by

something alive here on Venus. If it’s

alive and it helped you, it’s obviously intelligent, and that means that it has prior claim to Venus. And that means that

you – your station, your cities, and by extension the whole human race – are interlopers

here. That’s what it means. No wonder your superiors made every effort to

ensure it didn’t happen. It’s a wonder they didn’t send you to a camp as

well...or maybe the tales we hear down on Earth about those are exaggerations

and fabrications. That’s it, isn’t it?”

Won dug into herself and found the ability to speak again. “What

do you want, Ma’am?”

“What do you think? I want these aliens...sorry, I forgot, we’re the aliens here.” Bhattacharya

tapped one of the rock samples for emphasis. “I want these...Venusians?

Venerians? These creatures. I want to see them, find out about them. That’s what

I want to do.”

Won stopped the crawler. She needed all her concentration

for this. “Ma’am...I can’t do anything to help you. If I did – ”

“Yes, I know. You’d be in the camp I mentioned...or dead.

But I’m not threatening you. I’m making you an offer.”

“What offer?”

“You’ve never been to Earth, but you could easily go there.

This isn’t the Moon or Mars – the gravity is almost the same as Earth’s. Unlike

someone who’s a born Lunarian or Martian, you’d have no problem adjusting. I

could arrange to take you back very easily, as a publicist for Venus. The only

thing is, you wouldn’t be coming back. Once you’re on Earth, I’d arrange for

you to find a job and a new identity, and you’d disappear. Or, if you want, you

could work with me. Nobody would dare touch you then.

“Think about it. You’re estranged from your parents, and

they won’t miss you. You’re young, beautiful, intelligent, and you deserve a

much better life than conducting people around this poisonous, overheated ball

of rock. Heaven’s sake, young woman, you’ve never even seen a clear sky, or the

sun!”

“A clear sky?” Won replied wryly. “Outside the cities, I’ve

never seen the colour blue. It doesn’t

exist on Venus in nature.”

“There you are, then,” Bhattacharya said briskly. “So we’re

agreed? Good, now take me to the Venusians.” Her voice hardened again. “One way

or the other, I’m going to get to them, you know.”

“I’m sorry, Ma’am,” Won said. “There’s one little problem.”

“Problem?” Bhattacharya’s brow wrinkled. “What problem?”

“After I got back, as you surmised, I reported to the

authorities, and they weren’t pleased. Only, they didn’t just order me to keep

my mouth shut, as you thought.”

“Oh.” Bhattacharya’s face went momentarily blank as she

digested this. “What did they do?”

“What do you think? The next day they went out with troops

and bombed the entire area. They blew up the Venusians’ burrows, and destroyed

every single one of them.” She drew a long breath. “There may be others...there

are, I’m sure, others...but I have no idea where to find them.”

“Hmmm...but you know where they were. And you could find the place again.”

“To what purpose, Ma’am?”

“The corpses, of course. If I could find even one, or part

of one, that would be proof. I am not giving up without proof.”

And she wouldn’t give up, Won realised. This was a woman

driven by obsession. “I’ll take you there, Ma’am, and perhaps we might find

something. But the Venusians...”

“Well?”

“They’re rock-based, Ma’am. They couldn’t be carbon and

water creatures, like us, and survive at such temperatures.”

“Obviously they couldn’t. They have to be silicon-based. And

so?”

“So, they’re just basically living, moving rocks. If you

find any parts, they’ll be rocks. Rocks which were once living, maybe, but

still....rocks.”

“You can learn a lot from rocks.” Bhattacharya tapped the

samples on the table. “Find the corpses for me, and you won’t regret it.”

The threat had never been so unspokenly clear. Won nodded. “Yes,

Ma’am.”

“Also, you know what?” Bhattacharya said casually. “I don’t

think I’ll be getting into the suit again. If even you could have an accident,

it seems to be a little...unsafe. I think I’ll stay in here and watch you on

the cameras while you look for the bodies.”

Won met her eyes. Messages flashed unspoken through the air.

Finally, the younger woman nodded.

“Yes, Ma’am,” she said.

**********************************************************

The thunder of the

departing ship seemed still to be echoing in Won’s ears as she drove the small

crawler out towards the Baltis Vallis. Right now, at this moment, Professor

Bhattacharya would be in her cabin, probably already planning to write the

research papers that would make her famous, and dreaming of all the secrets

that would be revealed from the oddly shaped rock fragments that lay in the

hermetically sealed boxes in the ship’s hold.

Those papers would never be written, because those boxes

would never be found. Won had passed the message to Ri’s husband, who worked in

immigration, and he’d had the material impounded at the last moment. Professor

Bhattacharya still had her samples from the “ruins”; she’d have to remain

satisfied with them.

Won had been fortunate. The army’s recent series of

exercises, which had caused so much controversy in Chikhalsi Geumseong, had

ended only a few weeks ago, but long enough that the shattered test area had

been left empty and abandoned. Poking around in the broken ground, she had soon

found enough oddly shaped and coloured rock fragments to satisfy Bhattacharya.

They wouldn’t stand up to any geologist’s scrutiny, Won had been sure – but then,

she had no intention of ever allowing them to be seen by a geologist. And so it

had turned out.

“All I’m asking in return,” she’d said to Bhattacharya,

whose eyes had been glittering avidly at the sight of the stones, “is that you

keep my name out of it. Say that you

found them while searching the ruins, and only afterwards, when examining them

on Earth, realised that they were the body parts of living creatures. That’s

all I’m asking, Ma’am.”

She’d taken all the leave due her, and called in a couple of

favours to requisition a crawler for her own, personal use. She hadn’t had a

holiday in a long while. She was now taking it, in the way that mattered to

her.

Ahead, she saw the crooked stone spire, poking like a finger

out of the ground. Once again, she wondered what kind of geological freak had

created it. Not that it was much of a mystery, by Venus’ standards; even after

all this time, her damned home planet – a hot poisoned ball though it might be –

was nothing but a world of mysteries.

Climbing slowly into the suit, she wondered what it might

have been like, to have gone to Earth, to have walked along a beach by a

breaking sea, under a blue sky or a full moon. She tried to imagine the feel of

rain on her skin, grass on her feet, a wind in her hair that was not filled

with poison and death. She thought about it and shook her head; it was an

enticing prospect, but there were things she couldn’t give up for all that.

The hard ground, transmitted through the legs of her

crawler, felt good, small stones crunching under the three-pronged claws. She

ignored the crooked rock spire, and the hole into which she’d fallen, and which

had already half-filled with blown dust. She knew what she was looking for, and

in only a short while she found it.

“I’ve come back,” she said casually. “I know you probably can’t

hear me, and if you did you couldn’t possibly understand, but I came back to

say thanks. And I came to tell you that I’ll always do everything I can to

protect you.”

There was no answer, but she felt as though there were eyes,

or something like eyes, looking at her, and ears that might be listening. “I

know this is your planet,” she said slowly. “I know we’re...guests, I might

say, or even parasites. But there’s enough of this world for us two species to

share it, don’t you think? Our government has decided to hide the fact that you

exist, but it won’t harm you. Even the military exercises that were held some

time ago were cut short so none of your colonies would be damaged. And you...and

you, I know, won’t harm us.”

Something stirred, slow movement displacing soil, and she

smiled. “So you do understand me in

some way,” she said. “I wonder what you think of us, sopping wet morsels of water

and carbon, so alien to this world of yours that we must hide ourselves in

moving refrigerators simply so we can survive? And, compared to you, we must

have such astonishingly short lives. How old are you – a hundred thousand years

each? Ten million? Do you talk to each other about us? I wish I could know the

answers – but then the knowledge might leak out, so it’s maybe better not to

know.

“Out there...” She pointed up with one of her suit’s limbs

at the clouds. “Out there is a world filled with creatures like me. They have

other planets they could explore, make their own, and use as they see fit, but

they aren’t satisfied. Even though they hate this world, they intend to scrape

and gouge at it until they force it to give up all its secrets. But those

secrets belong to you, and it’s not right that anyone should have them.”

Something heaved in the ground, packed soil and small stones

falling away. Won smiled, watching. “I wonder what it was that made you save

me,” she said. “Was it just out of curiosity, or did you feel compassion for

me, this fragile little animal cowering in the cold, terrified of the world

which you find so natural to you? Was it the same impulse that leads me to

rescue a spider when I find it trapped in my kitchen sink – or did you do it in

the hope it would lead to something more?”

One by one they were rising out of the ground now, their

smooth, stony, blackish-red surfaces gleaming faintly in her suit’s lights,

balanced on thick projections like stumpy legs. The nearest reached out with a

tip to gently poke her suit’s leg, like someone patting a child reassuringly,

or a dog.

“Come to me,” Won said, and from all around, they came.

Copyright B Purkayastha 2017