Friday, 2 October 2015

Thursday, 1 October 2015

Wednesday, 30 September 2015

ISIS in Bangladesh

Today, I read that ISIS just killed an

Italian aid worker in Bangladesh.

To be honest, this was not entirely

unexpected. I have been anticipating for a while that ISIS would set up shop in

that nation; in fact I was mildly surprised that they hadn’t already done so.

The reasons aren’t that difficult to see.

The nation of Bangladesh was always an

artificial one. Back in 1947, when British India was vivisected into Pakistan

and the new independent India, the Indian province of Bengal was messily cut

up, broadly but far from entirely along religious lines, into the Indian state

of West Bengal and East Pakistan. This, of course, wouldn’t have happened if

the Muslim Bengali-speaking people of what became East Pakistan hadn’t demanded

it. In the new Pakistan, they thought, they would be free. But, as they very

soon found, all they did was exchange an equal status with Hindu Bengalis in

undivided India with subservience to the Urdu-speaking Punjabis and Sindhis of

West Pakistan, which, despite its smaller population, was the dominant partner

in the relationship. By 1970, East Pakistan had developed little if at all, the

people were poor, and they blamed all their problems on West Pakistan’s

tyranny.

Actually, this was inevitable. East

Pakistan was almost entirely agricultural, as all the industrial and commercial

centres, as well as the most important transport links, were in the part of

Bengal that went to India. But in the 24 years after East Pakistan’s independence

from India the new half-nation seemed to have been neglected so much that it developed

not at all.

To what extent this is true is debatable.

The Indian writer Sarmila Bose, in her book Dead

Reckoning: Memories of the 1971 Bangladesh War, suggests that the West

Pakistanis tried at least to a certain extent to develop East Pakistan, but it

was simply too poor, too isolated, and the difficulties in communication and

logistics too great to allow rapid development.

As usual in these cases, the development

that did occur helped only the educated urban elite. The poor in the villages

remained where they had been a hundred years earlier. Then, in 1970, the new

military dictator of Pakistan, Yahya Khan, announced what was definitely the

first free and fair election in Pakistan’s history. Predictably, given the

demographics, the majority of seats were won by the East Pakistani Awami League

of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman – an ethnic Bengali

party. This roused the ire of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Pakistan’s prime minister,

who refused to cede power. Mujibur Rahman began to make bellicose public

speeches threatening secession. Armed Bengali mobs attacked and massacred ethnic

Biharis – who were not even West Pakistani, but migrants from India – and any

West Pakistani they could find. Yahya Khan responded by launching a savage

military crackdown in March 1971. Tens of thousands of Bengalis fled to India,

where the Indian government at once set up training camps for a growing

separatist insurgency. By mid-1971, Indian forces were fighting inside East Pakistan,

launching hit and run attacks on isolated Pakistani units; and, on 22nd

November, India launched a full-scale invasion of the territory.

Why did India do this? Partly, it was the

pure desire to weaken Pakistan at any cost whatsoever. Also, the then Indian

prime minister, Indira Gandhi, saw an easy way to gain popularity ahead of an

upcoming election. After all, the isolated and badly outnumbered Pakistani

soldiers in the east could hardly provide serious resistance to India in case

of a war. Besides, the horror stories told by the floods of refugees – blown up

by themselves, and then again in the media – inflamed public opinion to an

extent that “something had to be done”. A lot of these refugees were East Pakistani

Hindus – but, as Bose says, the majority of them had been forced out not by the

Pakistani army, but by their own Muslim neighbours, who took the opportunity to

loot their belongings.

It does not seem to have occurred to anyone

in power in India then that East Pakistan was a problem for Pakistan, and the longer the problem continued, the worse

things would get for Pakistan; and by

cutting off the territory, India was actually relieving the rump state of Pakistan of a major burden.

Now, far from all the East Pakistani

Bengalis had been anti-Pakistan. As usual in these cases, the vast majority

were neutral, their primary effort being to survive. A fairly small number,

mostly of educated urban youth with Marxist leanings, were for the secession

movement. And a significant portion was of fundamentalist Muslims, from among

whom the West Pakistanis raised a militia force called the Razakars. As the

Indian army advanced into East Pakistan and converged on the capital, Dhaka, the

Pakistani army was tied up fighting the invasion – and the Razakars let loose a

reign of terror, abducting and murdering professionals, intellectuals, and

anyone else who might be of use to the new country of Bangladesh.

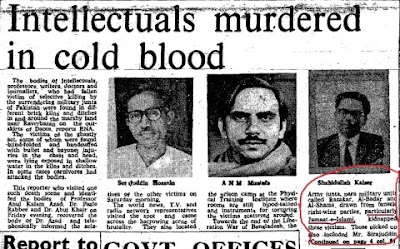

|

| Razakar victims [Source] |

By the middle of December 1971 the war was

over. Mujibur Rahman took over as the new ruler of the country. Naturally, the

problems that had led to the East Pakistanis growing disillusioned at the West

didn’t disappear. If anything, they intensified, because now even the links to

the western wing were severed, along with the markets and sources of

manufactured products that it provided. As is also the normal human reaction,

the Bangladeshis blamed everyone but themselves. An easy target for their ire

was India; by January 1972, a bare month after the end of the war, anti-Indian

sentiments were already on the rise.

Instead of harming Pakistan, India had

freed it of a burden and given it a reason to seek revenge; and, in the

bargain, it had gained an increasingly unfriendly neighbour in the east.

Mujibur Rahman was far from a good leader.

Soon enough, he had declared his own party as the only one in the nation, and in

1975 he and his family – all but a daughter, about whom we’ll speak in a while –

were murdered in a coup. In the original 1972 constitution, Bangladesh (despite

being about 90% Muslim) was a secular nation; but in 1977 the new military

dictator, Ziaur Rehman, declared Islam the state religion and lifted the ban on

Islamic parties. The old Razakars, who had disappeared in the aftermath of the

war, came crawling out of the woodwork and soon achieved considerable

influence. Ziaur Rehman was himself killed in a coup in 1981, and another

military dictator, Hussein Mohammad Ershad, took power. Ershad was ousted in a

popular revolt in 1990 led by two women. One of these two was the sole

surviving daughter of Mujibur Rahman, Sheikh Hasina Wajed. The other was the

widow of Ziaur Rehman, Khaleda Zia. Once Ershad was gone, though, these two

began bitterly feuding with each other, and their respective political parties,

the Awami League and the Bangladesh National Party, fought each other with

their respective goon squads, in and out of power. Today, it’s the Awami League

which rules, and the BNP is marginalised. But, of course, the situation of the

average Bangladeshi has improved not at all.

I had said the old Razakars were brought

back by Ziaur Rehman. The Muslim fundamentalists had flourished under the BNP,

and therefore the Awami League were against them. It began arresting some of

the more prominent among the Razakars who had been living openly for decades,

and has hanged a number on “war crimes” charges. It didn’t escape anyone’s

notice that the perpetrators of the massacres of Biharis and ethnic West Pakistani

civilians were never charged.

By the early 2000s, a new wave of Islamic fundamentalism

was sweeping Bangladesh. A lot of this came from the very large number of

Bangladeshis who lived and worked in the Gulf, particularly Saudi Barbaria, and

got infected with Wahhabism. Some of it also came from domestic disgust at the

corruption of the old Razakars, living in comfort – those of them who weren’t

arrested and executed, that is – and the ineptitude of the government. Soon,

there was a growing fundamentalist terrorist movement in Bangladesh, which

launched spectacular but fairly ineffectual attacks in the towns, while

murdering secularists, leftists and other undesirables in the countryside.

One major target was the increasingly

vulnerable Hindu community, who, ironically, found that they’d been better off

under Pakistan than they were in Bangladesh. Temples were attacked and

destroyed, Hindu women abducted and raped, and once again Hindu refugees began

streaming across the border into India. This time, though, the Indian

government’s reaction was total indifference.

Among the prominent Islamic Holy Warriors

was one Siddiqul Islam, popularly known as Bangla Bhai (Bengali Brother). The

military commander of a terrorist outfit grandly called the Awakened Muslim

People of Bangladesh (JMJB), he was finally captured in 2006, tamely

surrendering after being injured in a bomb blast. In a move of incredible

stupidity, the government executed him in 2007, along with several other

Islamic fundamentalists, thereby not just washing away the stain of his

surrender but immediately promoting him to the rank of martyr. The terrorist

movement went temporarily underground, but was far from destroyed. And, as time

went on, the fundamentalists began asserting themselves again, hacking to death

several atheist bloggers in recent times, among other victims. The Awami League

government seemed, and seems, more interested in keeping the BNP at bay than

defeating the fundamentalists.

|

| Bangla Bhai on capture [Source] |

As the state of Bangladesh weakens

steadily, therefore, the fundamentalists are gaining influence, feeding off the

resentment of the people at the government; a resentment at least partly the

result of the very artificial nature of the country, which doomed it to poverty

from the start by amputating it from India. The government itself is concerned

virtually entirely with its own survival. The BNP is itching for revenge

against the Awami League, and not particular how it gets it. Wahhabi influence

is rising. And with increasingly uncertain weather patterns, the consequence of

global warming, things for Bangladesh – a low lying agriculture-dependent

country – can only get worse.

Can you imagine a more fertile ground for

ISIS? Can you wonder why I was surprised they hadn’t moved in already, especially since it's not exactly a secret that they have Bangladeshis among them?

|

| Alleged British ISIS member of Bangladeshi origin, Rakib Amin [Source] |

Let me make a few predictions here. Please

understand that these are only my opinion, and in no way do they pretend to be

a cast-iron prophecy for what is to come:

1.As ISIS is pressurised in Syria and Iraq,

especially by the recent Russian entry into the war – and Russia does not mess around – it will try and spread

into other territories. The technique is the same as a metastasising cancer:

even if the original source is totally excised, it will start up again

elsewhere.

2. For a new place to expand into, Bangladesh

is a sitting duck for ISIS. The JMJB and other fundamentalist terrorists will

instantly flood to its banner. Bangladeshi citizens who have been trained by

ISIS and have fought for it in Syria and Iraq will come home and train more

members (in fact, as I’ll talk about in a moment, they almost certainly already

have). They will have, with ISIS’ funds and resources, far better weapons than

the tiny bombs and crude guns that the JMJB had. And, most important of all,

they’ll have a cause and an idea – something to aspire to, a goal that’s

greater than themselves. Whether this is even possible or not is not as

important as the idea itself. All revolutions in history ultimately grow out of

an idea.

3. By its own actions, the government of

Bangladesh has provided the Islamic State with a ready-made collection of

martyrs, who can be readily harnessed into the propaganda effort. Also, again

by its own actions, it’s created a powerful political enemy thirsting for

revenge, which more likely than not will cheerfully ally with ISIS if that

means damaging and bringing down the Awami League. Yes, I am saying that Khaleda

Zia’s BNP will prefer to side with ISIS against Hasina Wajed. South Asian

history has showed that we always side

with our greater long term enemy against our smaller, immediate enemy. Always.

4. Therefore, once ISIS secures a foothold –

once, not if – the state of Bangladesh is pretty much doomed. Peripheral

areas like the Buddhist Chakma tribes of the eastern hills, who fought a failed

secessionist war with Indian help, will once again try to break away. The

government will react with all the agility of a soggy biscuit. It will soon

lose control over large areas of the countryside, and be isolated in the

cities. Car bombs and assassinations will become daily news in Dhaka. Attempts

to send the army into the villages to conduct sweeps will fail. If these

missions are made in force, ISIS will keep its head down until the soldiers

leave. If they attempt to secure the area, they’ll be ambushed and attacked in

their bases. The more they try to control, the less they’ll end up controlling.

5. What will the government do then? Appeal

to India for military aid? That will at once paint it as a traitor to even the

neutral Bangladeshis. And it’s hardly clear that India would even send aid. It

would certainly not send troops,

because that would at once make it into an occupation army in a country where

the people already hate it. Any weapons it might provide, as it did to the army

of Nepal during the civil war in that country, would more likely than not be

swiftly seized by the insurrection. And, quite frankly, I don’t see Bangladesh

as being important enough for any other

nation to send forces there. It’s got no oil, no mineral wealth, minimal

strategic importance, and not much of a voice in world affairs anyway.

Che Guevara wrote that a guerrilla war

develops in certain clearly demarcated phases. The first one is ideological

indoctrination and recruitment. That, in substance, already exists in

Bangladesh. The Razakars and the JMJB have already prepared the way for that,

and, in addition, the Gulf Bangladeshis and their Wahhabi ideology can only

help. Remember that – again – they don’t have to recruit everyone. The majority

of people will be neutral and try just to survive.

The second phase is training. A lot of

this, again, already exists, both in terms of what Bangla Bhai and his gang

achieved. The groundwork is already there; ISIS merely has to build on it.

The third phase is hit and run attacks, building

up to creating “liberated areas” where the government can’t operate freely and

where its writ does not run. The fact that ISIS has already launched at least

one attack is proof that it’s at least arrived at this stage.

The fourth is the phase of full

conventional war, designed to try and defeat the government forces in the field in

battle. That is the stage where ISIS is in Syria and Iraq – or where the

Taliban are in Afghanistan. If and when it comes to that, India might step in – might, with air strikes,

try to turn the tide. But what good that would do is doubtful. And long before

that stage, ISIS would most certainly have got active on Indian territory as

well, so one can safely assume that India will have more important things on

its mind than what happens in Bangladesh.

All this is of particular interest to me,

you see, because I am an ethnic Bengali, and because I live not far from the border;

just about sixty kilometres from Bangladesh. When they come, they'll come here first. The car bombs will go off in the streets of this town.

Of course, I may be wrong, and this ISIS

attack might be only a flash in the pan.

But I’ll wager, against my own hopes and

inclinations, that I’m right.

Tuesday, 29 September 2015

Monday, 28 September 2015

The Weapon

The night was black and silent, but the

darkness and silence would not last long.

The warrior was uneasy. He was still very

young, so young that the others laughed at him and said he was still a

hatchling. But he was old enough to have been put on guard duty, and in these

last hours before the beginning of history.

That was what the senior commander had

called it that morning: the Beginning of History. “Today,” he’d said, “history

begins. And you’re all privileged to be here to see it.”

The young warrior did not feel privileged.

He just felt very nervous, and very cold. It was a cold night, like all the

nights, but he felt colder than that.

A shadow loomed, a dark silhouette picked

out against the stars, and the warrior slapped the stock of his weapon. “Halt,”

he said, hearing the tremor in his own voice. “Halt and give the password.”

It was the junior commander, out on his

rounds. An older, experienced warrior, he snorted at the uncertainty in the

young one’s voice. “You don’t even sound like you mean what you’re saying,” he

said. “All an enemy would have to do is shout at you, and you’d stand aside and

let him go past. It’s lucky the war’s ending tonight.”

“Is the war ending tonight, then?” the

young warrior asked, grateful for the darkness that covered the heat of

embarrassment that coloured his skin.

“What do you think?” The junior commander jerked a digit at the angular mass

of blackness that they were guarding. “Once that thing in there gets going,

there will be nothing the other lot can do but pray.”

“Have you seen it?” the young warrior

asked, in lieu of answering the question. The junior commander tended to expect

answers even to rhetorical questions. “...Sir,” he added belatedly.

“I escorted it, didn’t I? I was in the

escort that brought it here and guarded it while it was being assembled.”

“What was it like?” the warrior asked, and

instantly feared that he’d gone too far.

The junior commander seemed to be in a good

mood, though. “It was just like an egg,” he said. “The core of it, I mean. A

shining, silvery egg, about so big.”

“And that will...wipe out the enemy? End

the war?” The young warrior found it impossible to believe. The war had been

hanging over his parents’ heads since long before he’d even been hatched. “Really?”

“They won’t even have time to scream,” the

junior commander said with relish. “We’re going to hit them with thousands of

these. Burn them all to a crisp. Tomorrow you’ll be out of uniform and back on

your farm.”

“I’m from the city,” the young warrior

protested.

“City, farm, whatever. The main thing is,

you’re never going to actually have to fight.” The junior commander glanced

back at the angular building. It was no longer quite as dark as before. Tiny lights

moved back and forth. “They’re getting ready,” he observed.

“What...” the young warrior hesitated. “What

does it do?”

The junior commander rumbled a cough. “I

shouldn’t actually tell you this,” he said. “It’s still secret. But there’s nothing

you could do now, even if you were a spy.”

“I’m not a spy!” the young warrior

protested. “...Sir.”

The junior commander laughed. “Of course

you aren’t. Nobody in their right minds would use someone as half-hatched as you

to spy. Well, I have a friend, who’s posted out in the western desert, where

they tested one of these. He showed me pictures of what it did.”

“And?”

“Just take it from me: you don’t want to

know. They used only a small one, but they tested it on a town, you see.”

“A town? But...”

“They had to be sure it worked. And it did,

even better than expected. That’s why

I know that the other lot are done for.”

“But...” the young warrior repeated, not

sure of what he wanted to say. “The people...the eggs...”

“Would you rather fight or be safe at home?”

the junior commander asked him. “Well?”

“If you put it like that...safe at home, of

course, sir.”

“And tomorrow you will be. That’s a

promise.” The junior commander rumbled again. “Your parents will be happy, I suppose?”

“Well, yes, sir. They didn’t want to see me

go to the army, but they didn’t have a choice.” The warrior hesitated. “I don’t

think they’d have hatched me at all if they hadn’t been ordered to by the government,

to tell you the truth.”

“More than likely they were ordered to. But

then we were getting ready for a long war, and nobody could have predicted that

we’d have this weapon then, and be able to finish the war at a stroke, even

before it started. Not even the scientists knew.”

“I just have a feeling...” The young

warrior felt the heat of embarrassment again. “I don’t know how to say it. But

the others...they haven’t actually gone to war against us, have they? They

haven’t done a thing to harm us in any way. It’s only we who have been getting

ready all these years to harm them.”

“Don’t fool yourself,” the junior commander

said. “They’d do exactly the same to us, if they got a chance. Only the fool

waits for the enemy to make the first move.”

“But they don’t even know we exist.”

“All the more reason to press our advantage

while we still have it, hatchling. Didn’t you hear what the senior commander

said today? And don’t you think they’d use the weapon on us, if they’d

discovered it first?”

“But they aren’t even the enemy, not

really. Not until they fight us. Sir.”

“I’ve seen fighting,” the junior commander

snapped. “And, believe me, anything that spares me from having to do it again

is fine with me. Anything at all.”

The young warrior shifted restlessly but

was saved from having to answer by a red light that glowed momentarily from the

angular mass of the building. “It’ll be away soon,” he said.

“Yes.” The junior commander’s voice took on

a dreamy tone. “Can you imagine them, right now, at this very moment, going

about their business, maybe preparing their weapons, making themselves ready to

attack us someday, and then, suddenly, they simply aren’t there any longer?

Wiped from existence? And the threat to us is gone, gone forever.”

The young warrior opened his mouth to

reply, but was interrupted by a noise. It began as a low, grinding roar,

swiftly built up to a howl, which rose to a scream that tore the night asunder.

A light grew from the building, a red glow that grew orange and yellow and then

white, and then it rose into the air, a white incandescent ball of flame. The

nightmare shriek of its passage was still echoing from the land as it

disappeared into the darkness above.

“There’s another,” the junior commander

said, pointing to the horizon, where another ball of flame rose, and another

beyond that. From all around the blazing fireballs leaped into the sky, their

fading howls echoing back and forth in the darkness. Finally the last one had

gone, and the night was silent again.

“Well, that’s that,” the junior commander

said with satisfaction. “Aren’t you grateful you aren’t on the receiving end of

that lot? Now we can go on with our

lives.”

“And they won’t have any more lives to go

on with.” The young warrior hesitated again, and then decided he had nothing to

lose. “Sir?”

“What?” Now that the weapon had gone, the

junior commander’s good humour seemed to be evaporating fast. The young warrior

suddenly realised that he’d been nervous as well, and needing to talk. “What is

it?”

“I just had a thought. Suppose...suppose

some other race finds us, has found

us at this very moment, and decides to wipe us out before we could be a threat

to them? Then what?”

The junior commander laughed shortly. “That

could never happen. The sensors in the building there, and all the others, they’re

scanning everything, all the time, without cease. We’d find anything before it

could find us. Besides, the gods were good to us, to discover the enemy first

and to let us invent the weapon to wipe them out. Why would they not be kind to us again? Tell me that.”

“Yes, but, still...”

“Get back on guard, warrior. Leave the

thinking for people paid to think.” The junior commander glanced up at the sky

one more time and went on his way.

Left alone, the young warrior shifted

uneasily. He thought of the enemy, still oblivious, the enemy who was still not

the enemy and would no longer be the enemy this time tomorrow. And he thought

about tomorrow, with a little spasm of pleasure. He had not been happy in the

army, and it would be good to be going home again.

Then he threw another look up at the sky,

obscurely worried that his words to the junior commander would come true and

there would be weapons hurtling down, from an enemy of whose existence they

knew nothing.

But mostly he shivered. The night was

really very cold.

He longed for the morning.

Copyright B Purkayastha 2015

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)