Sunday, 1 April 2018

Operation Rook: Douglas MacArthur And The Plot To Nuke North Korea

It was a

bleak morning in April 1951 over the cold Sea of Japan. High over the ocean, just

off the North Korean coast, a United States Air Force B29 bomber of the 9th

Bombardment Wing was flying in slow circles. The increasingly anxious crew was

waiting for their escort fighters and support team of B29s to rendezvous with

them, while watching their fuel gauges drop lower by the minute.

The B29 was weighed down by the immense

weight of a Mark 4 nuclear fission bomb. Its destination: Pyongyang, capital of

the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

At the same time, a MiG15 fighter of the

Chinese People’s Liberation Army Air Force took off from Antung air base in Manchuria for

a routine patrol over North Korea. The pilot, Wang Zhejian, was on his first

combat mission.

On or about the night of 24th

June 1998, the North Korean trawler Dae

Yong Su39 snagged something in

one of its trawls. Pulling up the net, the crew discovered that they had caught

a large piece of aircraft wreckage. Markings on the wreckage caused the captain

to report it to the authorities by radio at once. Within a couple of days,

Korean People’s Army – Navy (KPAN) vessels had retrieved the wreck, and

discovered something within it that had profound consequences for the nation’s

defence programme.

What happened when Wang Zhejian’s MiG15 met

the 9th Bombardment Group B29, and the Dae

Yong Su39’s discovery decades later, would change the course of history – but

the story has been kept under wraps for almost seventy years.

Now, at last, it can be told.

********************************************

On 11th

April 1951, in the middle of the Korean War, President Harry S Truman abruptly

“relieved” his military commander in Korea, General Of The Army Douglas

MacArthur[1].

This dismissal, which is rather famous in

military history, was explained as stemming from MacArthur’s public

contradiction of Truman’s official statements on Korea – and, as became evident

later, by MacArthur’s own admission – owing to his demands to use nuclear

weapons on North Korean and Chinese targets, something that alarmed even the

British government.

Background:

MacArthur was one of the more bizarre

military figures of history. A shameless self-promoter, he had initially

opposed the use of the atom bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and had only been

informed of the existence of the atom bomb a few days before it was dropped,

even though he was the theatre commander in the Pacific in mid-1945[2].

He had subsequently been made the de facto dictator of Japan, ruling the

defeated country in the immediate post-WWII years. As the Korean War began, he

had been declared the commander of “United Nations” forces (meaning what would

today be considered NATO troops, because the composition was virtually the

same) in Korea.

On 15th September 1950, with

“United Nations” forces and their South Korean allies having been driven into a

small perimeter around Busan in the south east of the Korean peninsula,

MacArthur launched an amphibious invasion of Inchon on the western Korean

coast. This succeeded, driving the North Koreans back over the pre-war

frontier. The so-called “United Nations” brief had been to “defend South Korea

against a North Korean invasion”; it had no explicit mention of crossing over

the 38th Parallel between the two parts of Korea and uniting them by

force.

MacArthur, however, had already been

privately informed by the Pentagon that he had carte blanche to cross the 38th

Parallel if he thought it “strategically and tactically necessary[3],

something, of course, that he correctly interpreted as licence to carry the war

where he wished.

As more than one voice had predicted, this

provoked a Chinese intervention; Mao Zedong famously stated in Beijing that

“when the lips are cut away, the teeth feel cold”, in recognition of the fact

that if North Korea was allowed to be destroyed, China would be the next target

[vide Russell Spurr, Enter The

Dragon: China At War In Korea]. MacArthur, faced with statements that the

Chinese would intervene, dismissed them out of hand during a meeting with

Truman in October 1950[4]. China, he stated, could only get fifty to

sixty thousand troops across the Yalu river (the border between China and North

Korea), and if they “tried to get down to Pyongyang” (by then captured by the

“United Nations” forces) “there would be the greatest slaughter”. In fact, the

Chinese had already crossed the Yalu, and by November had a hundred and eighty

thousand troops in Korea. Soon, they had annihilated MacArthur’s so-called End

The War offensive, retaken Pyongyang, and sent the “United Nations” forces

reeling back south of the border, again capturing Seoul.

On 30th November 1950, as

Chinese forces were counterattacking the “United Nations” and rapidly pushing

it back, Truman suggested at a press conference that the use of the atom bomb

was under “active consideration”, that the use of the atom bomb did not require

United Nations authorisation, and that the “military commander in the field”

(MacArthur) had discretion to “use...the weapons, as he always has”[5]. This was contrary to not just sanity but even

to US law, specifically the Atomic

Energy Act of 1946, which made compulsory the civilian control of nuclear

weapons[6].

Nine days later, MacArthur demanded

permission to employ nuclear weapons, and on the 24th December,

submitted a list of “retardation targets” across not just North Korea but

China, on which he proposed to drop 34 nuclear weapons[1][7]. He

also, vide General Courtney Whitney,

considered dropping radioactive waste along the North Korean/Chinese border,

but – presumably aware of the outcry if this was stated in public – did not

submit the proposal to the Pentagon.

It is obvious that had he taken this

action, he would have justified it post

facto by claiming that the authorisation to use nuclear weapons at his

discretion extended to using radioactive waste, and that the Pentagon would

have approved it. And – whatever his public posture – MacArthur was desperately

eager to use both the nuclear bombs and the radioactive waste. As he was to

state in an interview, on 25th January 1954[1][8],

“I

could have won the war in Korea in a maximum of ten days...I would have dropped

between thirty and fifty atomic bombs...across the neck of Manchuria...It was

my plan to spread behind us – from the Sea of Japan to the Yellow Sea – a belt

of radioactive cobalt...from wagons, carts, trucks and planes...The enemy could

not have marched across that radioactive belt.”

In other words, MacArthur was willing to

destroy the north east of China and turn North Korea into a radioactive wasteland

to “win” his war. Even by the standards of the time, when nuclear winter was

not a concept that had yet been thought of, this was arguably the standpoint of

a psychopath.

The Soviet Nuclear Bomb:

By 1951, though, the international balance

of power after WWII had drastically changed. While the USSR had been discussing

the construction of a nuclear weapon since the mid-1930s, and the physicist

Georgy Flyorov had written to Stalin in 1942 warning that the German enemy and

the Western “allies” were both working towards such a weapon, the exigencies of

the war meant that it was only after the atom bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

– which have been called “the opening shots of the Cold War[2]” –

that the USSR began actively pursuing a nuclear weapons programme. With the aid

of considerable and effective intelligence about the American and German

nuclear weapons projects, the USSR was able to carry out its first successful

nuclear test – the RDS-1 – on 29th August 1949, a full four to five

years before American and British intelligence had predicted that they would be

able to develop such a weapon[9].

The weapon was also deliverable, not just a technology demonstrator. During the course

of the war, the USSR had just one relatively modern long range heavy bomber –

the Petlyakov 8 – and because of the conditions of the fighting on the Eastern

Front, where planes were used at short ranges and low altitudes, it had not

wasted valuable time and effort in developing another. By 1944, though, with heavy

four engine American and British bombers pulverising German cities and American

B29s launching enormously long range firebombing raids over Japan, the USSR had

grown keenly aware that a long range strategic bomber would become necessary. The

increasingly obsolete Petlyakov was not the answer, and developing a new bomber

from scratch would take far too many years of effort, during which, Stalin was

increasingly convinced, his current “allies” would turn on him. That he was not

mistaken in this is obvious from currently available information, which proves

that both the American General George Patton and British Prime Minister Winston

Churchill (“Operation Unthinkable[10]”) were planning to begin a war

against the USSR as soon as Nazi Germany was defeated.

During 1944 to early 1945, four American

B29 bombers made emergency landings in Soviet territory while bombing Japan,

and a fifth crashed in Soviet territory after the crew bailed out. Since the

USSR and Japan were not at war at the time – war between the two was declared,

under the terms of the Yalta Conference, by the Soviet Union on 8th

August 1945 – the planes were legally impounded by the USSR. One was returned

when the USSR entered the war, but the other three were retained, and an

immediate effort was made to reverse engineer them and put a copy into service.

Despite a lot of hurdles – including the fact that the USSR used the metric

system, so Soviet sheet metal was of different thickness to American – the

reverse engineered aircraft flew in May 1947 and was inducted into the Soviet

Air Force, the VVS, in 1949, as the Tupolev 4. A nuclear capable version, the

Tu4A, was also developed simultaneously, and it was a Tu4A which dropped the

RDS-1 test bomb[11].

Neither the existence of the Soviet atom

bomb, nor the Tu4A, was unknown to the West, which knew that the Soviets not

only had the nuclear bomb but the ability to deliver it on American cities.

Therefore, by 1950, the nuclear bomb could no longer be used without risking

retribution in kind.

Whether Truman, whose knowledge of the

nuclear weapons he had unleashed on Japan was minimal, was aware of the import

of this, his military leaders at the Pentagon cannot have possibly been

ignorant of the possible consequences.

The Dismissal of MacArthur:

Meanwhile the war rolled on. Seoul, which

had been retaken by the North Koreans and Chinese, was recaptured on 17th

March, and on the 23rd MacArthur declared, on his own initiative,

that his forces would again cross the 38th Parallel, and rejected

any consideration of a ceasefire with the Chinese[1]. According to

Truman, this public insubordination (he had prohibited military leaders in

December 1950 from public comments about foreign policy) was the straw that

broke the camel’s back, and he decided to sack MacArthur.

There are excellent reasons to think that

this post facto justification was

just what is today called “arse-covering”; for Truman did nothing to remove

MacArthur at this time. Quite the contrary.

|

| Truman (left) and MacArthur, Wake Island meeting. MacArthur shook hands with Truman, his commander in chief, instead of saluting him. |

On 5th April 1951, the Joint

Chiefs at the Pentagon authorised MacArthur to attack Manchuria and the

Shandong Peninsula if the Chinese launched air strikes on him from there. The

next day, MacArthur met the US Atomic Energy Commission chairman, one Gordon

Dean, and arranged for the transfer of nine Mark 4 nuclear bombs to military

control[1]. These were loaded on B29 bombers of the 9th

Bombardment Group and flown to the US air base on Guam. Nominally, the B29s

were not under the command of the theatre commander, MacArthur, but under the

Strategic Air Command. In practice, MacArthur would, as we shall see, attempt

to force its hand.

It might as well be mentioned that the B29s

had previously been deployed on Guam in mid-1950, but been withdrawn. At that

time, though, their nuclear weapons had had an important component removed to

prevent unauthorised use; in 1951 this was not the case.

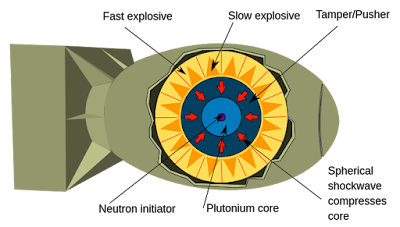

At this point it is necessary to briefly

discuss the Mark 4 nuclear fission bomb, which will play an important role in

the rest of this article[12].

The Mark 4, like the Nagasaki bomb (“Fat

Man”), and unlike the “gun type” Hiroshima bomb, was an “implosion” device.

This works by compressing a perfectly spherical core of uranium 235 or plutonium

239 by means of the simultaneous explosion of a surrounding spherical assembly

of explosive “lenses” until the atoms of the core undergo splitting.

|

| Schematic of an implosion type fission bomb. |

In early

bombs, like “Fat Man”, the core was placed in the centre of the shell of explosive

lenses and the bomb assembled before it was loaded on the bomber. The bomb was

then dropped over the target, and exploded at a pre-set height when barometers

in the casing detected the air pressure appropriate for the altitude.

There are obvious problems with this; if

the air pressure is for any reason different (for example, because of

variations in atmospheric humidity) the bomb might explode at the wrong

altitude, adversely affecting the damage radius or even potentially threatening

the aircraft and crew carrying out the attack. It is also possible that the

bomb might explode in case of an air crash while taking off or landing (if the

weapon was still aboard). Therefore, the Mark 4 introduced an important

innovation: the core (which was “composite”, meaning that it comprised, in this

model, both U235 and Pu239) was carried separately from the main bomb. Once

almost at the target, a particular crewman (known as the “weaponeer”) would

remove part of the casing and a segment of the explosive lenses underneath,

insert the core, and replace the lenses and the casing. Therefore the bomb

would be unlikely to go off prematurely, and if the bomb was unused the core

could be removed again before landing and the weapon made safe. When the B29s

had earlier been deployed to Guam – from 28th July to 13th

September 1950 – the cores had been left behind; this time, though, they were

deployed along with the cores, meaning that the weapons were ready to use.

All that was required was to fly to the

designated targets, install the cores, and drop the bombs.

Different models of the Mark 4,

incidentally, had different yields, which could vary very widely; all those

that were placed at MacArthur’s disposal had a yield of 21 kilotons, more

powerful than the Hiroshima bomb and as powerful as the one dropped on

Nagasaki.

MacArthur had one major, and extremely

significant, difference of opinion with the Pentagon on the very nature of the

People’s Republic of China[1]. According to the Pentagon, the PRC

was just an appendage of the USSR, a glorified satellite, little better than

Britain was to the US at that stage; therefore a nuclear attack on China, they

feared, would inevitably be interpreted as an attack on the USSR itself, and be

responded to accordingly. MacArthur, who had spent many years in Asia,

correctly considered the PRC to be an independent nation in no way beholden to

the USSR and only temporarily allied with it. That he was correct is, of

course, obvious; but the corollary – that the USSR would not respond to a

massive nuclear attack on China – is not. The massive use of nuclear weapons

just across the Soviet border would alone risk contaminating Soviet cities such

as Vladivostok with lethal amounts of radiation; and like China, the USSR would

be aware that if it allowed China to be defeated, the nascent NATO would be

emboldened to carry out the long desired invasion of the USSR itself.

That this was so should not have been

unknown to MacArthur, since Soviet pilots and ground crew were servicing and

flying MiG15s over Korea; obviously, whether China was a “temporary Soviet

ally” or a “satellite”, the USSR was invested in the Korean War and would fight

to defend China if necessary, since China was of much greater value than North

Korea. For whatever reason – tunnel vision or contempt for the Soviet Union –

MacArthur chose to ignore this fact.

Therefore, while to the Pentagon, the risk

of a nuclear war with the USSR had to be balanced against the “benefits” of

using the nuclear bomb, MacArthur had no such constraints; to him it was a tool

to be used and there were no consequences to be feared. This was an era when

racism against Asians was so ingrained in Western thinking that – as late as

1964 – the British historian David Rees could get away with writing (in Korea: The Limited War) that “the

conquest of the civilised world by millions of expendable Asians had turned out

to be a futile dream.” Therefore MacArthur felt no compunction at the thought

of massacring millions of despised Asian people with the nuclear weapons he

finally had at his disposal.

As shall be seen, he soon took steps to use

the tool he had been handed.

Meanwhile, MacArthur had not gone out of

his way to win friends in the US administration. While the account I have given

so far of this period might suggest that the US military and foreign policy of

this period was focussed on Korea, this was very far from true. The Truman

administration, in fact, for its own purposes, preferred to garrison West

Europe, which Stalin was allegedly about to invade and overrun. Of course, as

was evident even at the time, Stalin had no such plans; he had always preferred

to maintain the Soviet system in the USSR alone, and had merely occupied

Eastern Europe as a buffer to prevent another Operation Barbarossa-style

invasion of the Soviet heartland. But for the Truman administration,

maintaining military control over as much of Europe as possible took precedence

over the war in Korea. On 20th March, MacArthur wrote an embittered

letter criticising the Truman administration’s “fixation” on Europe, which was

made public on 5th April. At the same time, reports reached Truman

that MacArthur had contacted Spanish and Portuguese diplomats in Japan and

informed them of his plans to expand the Korean War into a conflict which

would, he said, result in “...the permanent disposal of the Chinese Communist

question”[1].

Obviously, this was insubordination of an

extraordinarily high order, and Truman could have been forgiven if he had

dismissed MacArthur immediately and without further delay. Instead, as

mentioned above, not only did he not do so, he, as stated above, permitted

multiple nuclear weapons to be placed at MacArthur’s disposal, if not under his

direct command. It was as though Truman was trying to get MacArthur to launch a

nuclear war, but absolve himself (Truman) of all blame for it.

Strangely enough, it was only on 11th

April – when a new offensive launched by MacArthur without permission from

Washington was pushing north of the 38th Parallel – that the general

was “relieved”, that is, dismissed. According to the conventional narrative,

Truman had planned as early as 6th April to dismiss MacArthur, but

the next several days passed in discussions with his Pentagon generals and

cabinet members on whether this should be done. Only on the 9th, the

story goes, did Truman secure the “concurrence” of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to

fire MacArthur, and even then he waited two days longer, until the 11th,

before putting it into writing.

There is excellent reason to believe that

something else happened during these days which actually precipitated the

dismissal, and that the “insubordination” of MacArthur, which had been going on

unpunished for so long, was only a convenient excuse.

To understand what that thing was, we will

now turn to the story of a B29 called Flying

Flimflam, and the events of 8th and 9th April 1951.

*****************************************

So far in

this article, I have cited information available in the public domain; from

this point onwards I will be reviewing the account of a remarkable and

extremely well-researched book. This is Operation

Rook: Douglas MacArthur and the Nuclear Strike on North Korea, by Harold

O’Brien and Alan Xavier, Überhaupt Publishers, Quatsch, Germany, 2018, 389

pages (including 40 pages of end notes).

The authors of this book state their

purpose at the start: to explore the real reason behind MacArthur’s dismissal,

and to throw light on the hitherto carefully suppressed tale of the attempt by

the general to start off his planned campaign of nuclear attacks across North

Korea and China – and how it failed, and why.

The qualifications of the authors are given

in the foreword: Harold O’Brien is an aviation historian who has worked, among

other places, at the Smithsonian Institution. Alan Xavier is an aeronautical

engineer and writer who speaks both Korean and Chinese and has lived and worked

in South Korea and China.

Xavier says he became interested in the

topic when he met a man whose grandfather, Wang Zhejian, had been a MiG15 pilot

in the Korean War. Out of curiosity, he met the old man, who, among other

things, described an aerial battle that took place on 9th April 1951

off the Korean coast. Intrigued, Xavier conducted a series of interviews with

other surviving former Chinese MiG15 pilots and ground crews from the period.

Later, seeking corroboration from the US side, he contacted O’Brien, and their

further research led to revelations they detail in this profusely annotated book.

This is what they found out.

*****************************************

On the 6th

April 1951, Douglas MacArthur met, as described above, the US Atomic Energy

Chairman, Gordon Dean, and arranged for the transfer of nine Mark 4 nuclear

bombs. The next day, ten B29 bombers of the 9th Bombardment Wing

took off from Fairfield-Suisun Air Base in California and flew west across the

Pacific to Guam, arriving in the early evening; nine of them carried a Mark 4

bomb each, with the core stowed separately in a “birdcage”. The tenth bomber

was loaded with electronic and photographic equipment intended to be used for

reconnaissance purposes and to measure the yield of the weapons if they were

used.

These bombers were all of the so-called

Silverplate or Saddletree series[13], which had been optimised to

carry nuclear bombs. They differed from standard B29s in several ways.

First, all their gun turrets (except the

tail turret) were removed, as well as all the armour plate, in order to reduce

weight. This permitted them to fly high and far enough with the enormous weight

of a Mark 4 atom bomb (approximately 4900 kilograms) to be able to reach

targets far away at an adequate altitude to make them difficult to intercept.

Secondly, their bomb bays and bomb release

mechanisms were changed to the British pattern – which had been used by British

heavy bombers in Europe – to allow faster and more effective unloading of their

single, super heavy, bomb, unlike the many lighter bombs other B29s carried.

Third, they had more reliable engines and

reversible pitch propellers for faster braking on landing (the propellers could

blow air forward and slow the aircraft once it was on the ground) to reduce the

chances of an aeroplane overshooting the runway and crashing, potentially causing

an explosion of an unsecured bomb.

Planes of the Silverplate series had been

used to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and it was the same series (now renamed

Saddletree) which were sent to Guam for possible use against North Korea and

China.

O’Brien and Xavier give exhaustive details

of the individual planes that were sent to Guam, including all their model and

serial numbers and the names of their pilots and chief crew members, but for

the purposes of this article we are concerned with only three – Hornswoggle

Hannah, Bluffmaster, and, most importantly, Flying Flimflam.

Flying Flimflam was a B29 (model number

B-29-48-MO, serial number 47-24681) manufactured in Bellevue, Nebraska, in the

same factory that had constructed the Enola Gay, which had bombed Hiroshima. It

rolled off the assembly line in July, 1948, and began squadron service the

following month after tests. It was given its name by its first pilot, Captain

Jack Murphy, and retained it after passing to a new crew in December of that year.

On 31st January 1949, while

cruising on the runway, Flying Flimflam suffered an explosion in the port

(left) outer engine and a resultant fire, which destroyed the engine and led to

the replacement of the outer section of the wing. There were no casualties, and

no definite cause of the fire was ever discovered. The plane was returned to

service on the 18th of the following month and for the rest of its

service had no other fires or engine trouble.

Flying Flimflam had been one of the

B29s which had briefly been sent to Guam in 1950, carrying bombs, as it will be

recalled, minus their fissile cores. It had flown there without incident (while

one of the other planes had crashed with the loss of all crew) and returned at

the end of its deployment. As such, it was one of the aircraft selected for

return to Guam. At that time it was on its fifth crew (not the one which had

flown to Guam earlier), under the command of Captain John Thomas; but the man

who would fly it into action was the mission commander, Colonel Michael “Mickey”

Finn.

Michael Finn was, in April 1950, thirty

years old. A native of South West Indle, Oklahoma, he had joined the air force

in 1943 after completing college, and qualified as a pilot in December of that

year. He was then sent to England, and flew B24 Liberator bombers over Europe

in 1944, successfully completing twelve missions before being recalled to the

United States to train on the new B29. In February 1945 he was posted to the

Twentieth Air Force, which at the time was involved in firebombing Japanese

cities. Finn flew B29s on 23 missions

between February 1945 and the end of the war, operating from Tinian against the

Japanese mainland, including Operation Meetinghouse[14] – the

firebombing of Tokyo on the night of 9th/10th March 1945

which killed between 80000 to 100000 civilians. Though he was not involved with

the 509th Composite Group which carried out the nuclear attacks on

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, after the war he was transferred to the 9th

Bombardment Wing, which flew B29 Silverplate aircraft and was meant to carry

out nuclear attacks. This meant, O’Brien and Xavier write, that he was of

exceptional ability, since only the best pilots were chosen for this duty.

This is certainly the impression given by

his promotion record. Finn was made Major in August 1945, and was asked to

remain in the Air Force when he, apparently, considered leaving after the war.

He was raised to Lieutenant Colonel in 1947, and promoted to Colonel in January

1949. And when the B29s of the 9th Bombardment Wing were sent to

Guam, he was appointed the mission commander, though this was usually the remit

of a brigadier general (brigadier in Commonwealth militaries) and not a

colonel.

As a person, though, O’Brien and Xavier

write, Finn was something of an enigma. He was not married, and seems to have

had no known romantic involvement. Nor does he seem to have had many friends;

aloof and quiet, he was known for rigid obedience of orders, a strict adherence

to rules, and sticking exactly to mission parameters and protocols. According to another officer quoted in the

book, Finn

“...was

the sort of man who gave the impression of being a machine; you told him what

to do, and he did it, ruthlessly efficiently but without either passion or

protest. You could see it in his eyes, too – when he looked at you, you got the

impression that he saw, not you, not the wall behind you, but something on the

far horizon. In all the time I knew him, I don’t think I ever saw him smile.” (Page

129)

This, then, was the emotionless officer chosen

to lead the bomber detachment, and to drop nuclear weapons on North Korea and

China. According to O’Brien, MacArthur had asked specifically for someone like

Finn to lead the bomber group – someone who would obey orders without being

bothered by emotional scruples. Apparently, after photographs of the burnt and

devastated survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had become public, MacArthur did

not want to take chances with any of his subordinates suffering a sudden attack

of conscience when ordered to inflict many times more suffering on the

civilians of China and North Korea.

On the same day as the 9th

Bombardment Wing planes reached Guam – 7th April – MacArthur had a

meeting in Tokyo, shortly after noon, with US Air Force Brigadier General

Edward P Humbug, in charge of coordinating the bombing offensive against North

Korea with the army. Humbug was on deputation from Washington; his permanent

assignment, in fact, was with Strategic Air Command. This meeting was very

strange for a number of reasons.

First, MacArthur had met Humbug in an official military situation

conference that morning at half past nine, and that meeting had gone on for

three quarters of an hour. There were, as far as can be determined, no

emergencies that would require a second meeting just two hours later.

Secondly, MacArthur had not arranged the meeting through his staff; at noon,

MacArthur had (in his capacity as de

facto dictator of Japan) been scheduled to receive a delegation of Japanese

businessmen. Fifteen minutes before the meeting, however – with the businessmen

having already arrived and waiting – MacArthur abruptly cancelled the meeting

and rescheduled it for a week later. (Since MacArthur had been removed from

command by that time, this meeting never, ultimately, took place.) Instead,

MacArthur asked his staff to send in a visitor who would be arriving at any

moment; this turned out to be Humbug.

Thirdly, the meeting was not arranged by Humbug, since at no time between

the morning conference and noon had MacArthur received any phone call, radio

message, or other communication from him. It is obviously MacArthur who had

arranged the meeting, either on the sidelines of the morning conference or

shortly afterwards.

Fourth, the meeting between MacArthur and Humbug involved the two of them

alone; no aides were present, and no voice notes of any kind were taken. The

meeting lasted about half an hour, and neither MacArthur nor Humbug mentioned a

single thing about what they had discussed to their respective staffs.

Fifth, after leaving MacArthur’s office, Humbug went straight to the airport

and arranged for a special USAF flight to Guam, on which he left within the

hour. He returned the next morning, and as for what he did in Guam, that we

shall shortly discuss.

At this point it is probably useful to

review the situation as it was on 7th April 1951:

1. MacArthur, who was obsessed with

“defeating communism” in Asia, had wanted to destroy North Korea and much of

North East China with nuclear weapons, and was frustrated that he had not been

allowed to carry this out.

2. His land offensive to capture North

Korea, his own vainglorious claims to the contrary, had ended in defeat and

stalemate. For someone of his extremely egocentric nature, this was

intolerable, and he was thirsting for vengeance.

3. MacArthur, by this stage, more than

likely believed himself above the civilian government and certainly more “clear

sighted” than the Pentagon bureaucrats in uniform and the politicians in

Washington. His own statements increasingly contradicted the official

Washington line, and he had increasingly taken to ignoring the official

“policy” and taking matters into his own hands in the conduct of the war.

4. By this stage, he cannot have been

unaware that he was living on borrowed time, and that he had to deliver the

spectacular victory he craved before the bureaucrats and politicians he

despised robbed him of it.

The only way such a victory was even

possible to achieve, by 1951, was to conduct massive nuclear strikes across

North Korea, if not also China, regardless of consequences; and for the first

time he had, at his disposal – even if not under his direct command – the means

to carry out such a strike.

5. The only thing that stood in the way of

his carrying out this strike was the pusillanimity, as he saw it, of the Truman

administration and the paper-pushers at the Pentagon, who were terrified of a

Russian nuclear response. MacArthur was convinced that the USSR would not respond.

6. Therefore, in order to prove to the

Pentagon and the Truman administration that he was right, that they were wrong,

and also to take a step that it would be impossible to back away from,

MacArthur logically required to launch a spectacular nuclear attack. The Communist capital, Pyongyang, which he had so ignominiously

been compelled to retreat from, was an equally logical target for obliteration.

This sixth point could be called

speculation, except for the mysterious meeting with Humbug and what happened

afterwards.

Arriving in Guam at about 5.30 pm local

time, Brigadier General Humbug refused to leave the airport, and waited by the

side of the runway for the 9th Bombardment Wing planes to arrive. The

planes touched down between a quarter to seven and half past seven in the

evening, with Colonel Finn flying the B29 carrying the photographic equipment,

by the name of The Great Gammon. As soon as Finn had left the aircraft, Humbug

met him on the runway, drawing him aside to talk for several minutes. None of

the rest of the crew of The Great Gammon could hear anything of what was said,

but the co-pilot, Captain Peter Willy, saw the brigadier general hand an

envelope to Finn. Shortly afterwards Humbug left the airport, and early the

next morning flew back to Tokyo in the same aircraft in which he had arrived.

It must be remembered that officially the 9th

Bombardment Group was not under the control of the theatre commander,

MacArthur, but of Strategic Air Command based in Washington. Humbug, however,

was not an army, but an air force officer; and he was seconded as liaison to

MacArthur from Strategic Air Command. It was, therefore, in his capacity as a

part of SAC (which he still officially was) that he had met Finn, and the

envelope he had handed over (as per the testimony of officers given to the

authors) contained nothing less than written

orders to conduct a nuclear strike against Pyongyang with a Mark 4 nuclear bomb

as soon as possible, and certainly within the next 72 hours. Who this order

was signed by is not certain, for no copy survives; it certainly contained

MacArthur’s signature, but whether Humbug had added his signature to it, or

confined his role to that of messenger, is unknown.

What is

known is the actions Finn took that very evening, as soon as the crew of the 9th

Bombardment Group had had time to eat and freshen up. Calling the captains of

all the ten aircraft to his room at the base, he told them that the SAC had

ordered a nuclear strike within the next three days on Pyongyang, and informed

them of, though he did not show them, the written order. Even without the

order, there would have been no question of anyone refusing. Finn then called

in weather data for the next three days.

The next day, the 8th, promised

clear skies above Guam, but broken cloud cover over the Sea of Japan, joining

to form very heavy cloud over the northern part of the Korean peninsula, which

would make accurate bombing difficult. On the 9th, the skies over

Guam would still be clear, but the clouds over the Korean peninsula would

move over the Sea of Japan, leaving Pyongyang uncovered. By the 10th,

the cloud front would be moving quickly south-eastwards towards Guam, and

tending to develop into a storm. Therefore, of the three days, the only one

that offered acceptable conditions for bombing was the 9th April.

Having decided that, Finn dismissed his

pilots for the night; whether he communicated his decision to Humbug is not

known. The authors describe their efforts to determine if Finn and Humbug met

or spoke again that night(Pages 143-5), but without success. Both

Finn and Humbug were on the base, though housed at a distance from each other,

in B (Finn) and X (Humbug) blocks. One source claims that a motor pool vehicle

was requisitioned to drive “a senior officer” to X block, but whether this

“senior officer” was Finn is unknown. O’Brien and Xavier argue persuasively

that, with Humbug on the base and available, it is most unlikely that Finn did not communicate the decision to him.

They also say that the very fact that Humbug remained at the base overnight and

did not return to Tokyo until the morning proved that he was waiting for the

decision; in this they are more than likely correct.

The

events of 8th April:

After Humbug had left for Tokyo the next

morning, Finn called another meeting of his aircraft commanders, in which the

status of the individual aircraft were discussed in detail. Three of the planes

– Artful Dodger, Masquerade Mary, and The Great Gammon – had experienced

equipment malfunctions during the flight from California that required repair

and servicing. From among the others, Finn soon selected four for the attack. They,

and their respective roles, were as follows:

Hornswoggle Hannah would be the weather

reconnaissance aircraft, checking on conditions over Pyongyang ahead of the

main attack.

Bluffmaster would be the photographic and

electronic monitoring aircraft, to take pictures of the strike and its

aftermath, and to measure radiation levels, both by means of atmospheric

filters carried by the plane and using equipment packages dropped by parachute.

Flying Flimflam would be the actual

bomb-carrying aircraft, with Knave Of Hearts as the back-up aeroplane in case

something happened to prevent Flying Flimflam from taking off on its mission.

|

| Flying Flimflam, photographed on the ground at Guam, 8th April 1951. Photo credit O'Brien/Xavier |

The bombs Hornswoggle Hannah and

Bluffmaster carried, along with their separated cores, were unloaded, and

equipment for their respective roles installed. At the same time, the bombs

carried by Flying Flimflam and Knave Of Hearts were dismantled and checked by

the respective weaponeers and assistant weaponeers, and reassembled. This was

done entirely by the 9th Bombardment Wing crews; no ground crew were

involved in any way, in order to preserve secrecy.

At approximately noon, Finn called the USAF

K-9 Pusan East air base, where F86 Sabre jet fighters of the Fifth Air Force

were stationed, and arranged for escort cover on the following day. During the

Hiroshima and Nagasaki attacks there had been no fighter escort, and the bombers, except for

some desultory anti-aircraft fire over Kokura, had faced no opposition

whatsoever[2]. But North Korea in 1951 was not Japan in 1945, and

unescorted bombers were at great risk from North Korean and Chinese fighters,

apart from anti-aircraft fire. Finn secured the promise of a squadron of F86s

as escort for what he termed a “special mission”; there is neither evidence,

nor any reason to believe, that the K-9 Pusan East base commander was informed

what the “special mission” was about.

After the bombs had been reassembled and

loaded, the four planes – the three primaries and the spare, Knave Of Hearts –

made brief flights to test their equipment and ensure that their engines,

radios and other systems were in good working order. The ground crew on Guam,

who were of course aware of the activity surrounding the planes, were not given

any explanation either, except for the statement about a “special mission”. The

base commander, Brigadier General Donovan Sleech, met Colonel Finn during the

day, but what the latter told him is unknown; there is no record of Sleech

having communicated it to anyone. Since Sleech was under MacArthur’s theatre

command, he did not have any discretion in the matter, but whether Finn even

informed him at all about the intention of carrying out the nuclear strike is

unknown. O’Brien and Xavier claim(Page 192) that this is unlikely,

going by Finn’s attempts to keep the planning on a strictly need to know basis.

Late that afternoon, Finn called together

the captains and main crew members (co pilots, navigators, bombardiers – “bomb

aimers” in Commonwealth air forces, the crewman who would actually drop the

weapon – and weaponeers) of his ten aircraft, and in consultation with them

drew up the crews for the attack. He himself, as mission commander, would fly

the bomber plane, Flying Flimflam. This plane normally had Crew D-42 assigned

to it, but on this occasion Finn made several changes. The regular pilot, Captain

John Thomas, would act as the co-pilot for the mission, but several other crew

members were taken from other planes. The full roster of the Flying Flimflam’s

crew for this attack was (vide

O’Brien and Xavier, Page 210):

· Colonel Michael “Mickey” Finn –

pilot, mission commander, aircraft commander

· Captain John Thomas* – co-pilot

· Major Albert Chisel –

bombardier

· Captain Johannes “Flying

Dutchman” van der Bedriegen – navigator

· Lieutenant Colonel David Dieb+

– weaponeer and reserve mission commander

· First Lieutenant Edwin Hadjut –

radar countermeasures operator

· Second Lieutenant Leo Varas –

assistant weaponeer

· Staff Sergeant Giovanni

Cretini* – tail gunner

· Staff Sergeant William Forbryterson*

– flight engineer

· Sergeant George Puska* – radar

operator

· Sergeant Richard Morder* –

assistant flight engineer

· Private First Class Charles

Gyilkos* – VHF radio operator

*The

names marked with an asterisk denote those who were part of the regular crew of

Flying Flimflam; thus it can be seen that fully half the crew, six men out of

twelve, were from other aircraft, and flying together for the first time.

+Lieutenant

Colonel Dieb was tasked with taking over command in case Finn was incapacitated

in any manner after the start of the mission but the attack was to go ahead.

|

| The crew of Flying Flimflam, 8th April 1951, at Guam. Colonel Michael Finn is at bottom row, far right. Sergeant Morder is missing in this photograph. Photo credit O'Brien/Xavier |

The crews of the other three B29s were also

finalised. While Knave Of Hearts, as the reserve bomber, was assigned another

crew of twelve, the two other planes – Hornswoggle Hannah and Bluffmaster – had

ten man crews since they had no bombs and would not be carrying weaponeers or

assistant weaponeers. Though all planes carried radio operators, their role,

unless there were emergencies, would be restricted to navigation (which will be

discussed below). Finn ordered total radio silence after crossing Japan to

maintain secrecy and the element of surprise.

It seems remarkable, but according to

O’Brien and Xavier, at this stage not

even all the crew members of the planes carrying out the actual mission were

informed that they would be dropping a nuclear weapon. Except for the

pilots, co-pilots, weaponeers, navigators, and bombardiers present at this

meeting, the other crew members apparently were allowed to believe that they

were carrying out a practice attack on the Communist capital with a high

explosive bomb (like the “pumpkin bombs”[15] used on Japanese cities

prior to the Nagasaki bombing), to see exactly how it was to be done and to

refine procedures for the future.

Meanwhile, Brigadier General Humbug had

returned to Tokyo, and reported to MacArthur in his office. The meeting was

brief, and once again there was no aide present and no records were kept.

MacArthur, thereafter, made no attempt to contact Guam, and went about his

business as usual.

The distance from Guam to Pyongyang is 3400

kilometres; at the cruising speed of a heavily loaded B29, some 470 kilometres

per hour, that represented over seven hours’ flight time even if the plane flew

along a direct route. However, to avoid Communist air defences, Finn intended

to take a northern route, intending to reach the North Korean coast at a point

north east of Pyongyang, and then turn south west for the final approach,

outflanking the fighters that could be assumed to be guarding the North Korean

capital against air attacks from the south. This would add over an hour’s

flying time. Finn wanted to be able to return to Guam and land while there was

still some daylight left, to minimise the risk of crashes. Since the return

journey could be made directly and at a faster speed without the weight of the bomb

and the fuel already burnt, Finn kept seven hours for the return journey.

On 9th April, first light on

Guam is at 5.00 am, and sunrise at 6.12 am. Full darkness falls at 7.45 pm.

|

| Daylight times at Guam, 9th April |

Finn

therefore had fourteen and three quarter hours of partial and full daylight to

carry out his mission. Keeping seven hours for the return journey, he had to be

over Pyongyang no later than 12.45 pm (Guam time). This would have normally

meant that Flying Flimflam would have to take off at the latest by half past

four in the morning, before dawn; but there was another complicating factor.

Of the three aircraft that were to take

part in the raid, Flying Flimflam, with its 4900 kilogram Mark 4 bomb and two

extra crew members, was by far the most heavily laden, and therefore the

slowest. Finn would therefore take off earlier than the other two planes, which

were faster, and rendezvous with them (and the escorting fighters) off the

North Korean coast, only just before turning south west to cross the coast and

begin the final attack. The rendezvous was known as Point Zeke, and was halfway

between Kimchaek and Singpo, just off the coast. Finn would have to take off at three in the morning.

All that was left was to choose a name for

the mission, and this had already been selected, either by MacArthur or by

Finn. At any event, he announced it at the end of the meeting. Eschewing any

ironic or boastful reference to victory or vengeance, the name selected for the

attack was simple and, on the surface, innocuous.

The nuclear attack on Pyongyang would be

simply known as Operation Rook.

9th

April: Operation Rook:

At seven minutes past three in the morning,

Flying Flimflam took off from Guam, in darkness but for the runway markers.

With the enormous weight of fuel and the bomb, it was an exceptionally

hazardous take off, and the bomber only lifted into the air at the very end of

the runway. Lifting slowly into the darkness, it set off to the northwest. It

would fly over the Pacific until it reached Japan, overfly the island of

Honshu, and then reach the Sea of Japan, whereupon it would turn due west until

it reached Point Zeke. It would then wait there, flying a holding pattern, for

the other planes to rendezvous with it. If everything went according to plan it

would not have to wait long.

It will be recalled that the weather was

the factor that had determined that the attack would be carried out on this day

of the three dates (8th, 9th and 10th April)

available. This was because the heavy cloud layer that had covered Korea on the

8th had moved out over the Pacific by the 9th, but not

yet reached the neighbourhood of Guam. By mid morning on 9th April

its western fringe still covered the Sea of Japan, but most of it was over the

Pacific, and gathering force into a storm.

If Finn had been able to, he would

undoubtedly have routed Flying Flimflam around the northern edge of the

weather, but fuel and time constraints – the storm extended as far north as the

island of Hokkaido in Japan – made this impossible. He therefore had to fly

through it, and not just through it, but where it was thickest and the

gathering storm winds most severe.

Until this point, everything known about

Finn and the Flying Flimflam, as O’Brien and Xavier point out, is verifiable

information from multiple sources; but from this point on, what actually

happened can only be inferred, because there is essentially no further

information available until the aircraft was sighted by Wang Zhejian in his

MiG15 hours later and far to the north west. Going by what is known, though,

there is little doubt as to what happened.

Several hours after leaving Guam, at about

seven in the morning, Flying Flimflam entered the cloud layer. From available

weather reports (cited by O’Brien and Xavier) it was much higher than

predicted, reaching an altitude of some ten thousand metres, too high for the

heavily laden B29 to climb over. For about two hours, Flying Flimflam flew

through the cloud and gathering wind. And

during these two hours, something happened that drove the B29 irrevocably off

course.

|

| Map from O'Brien/Xavier |

Before discussing what this something might

have been, and the result, it is necessary to briefly describe the navigational

aids Finn – or, to be exact, his navigator, van der Bedriegen – would have been

using. This was long before the era of GPS, and years before even the first

satellite, Sputnik, was launched. Navigation in that era depended on the same

methods ships had been using for centuries – navigation by the stars and dead

reckoning – and direction finding by radio.

Dead

reckoning works like this: if you know your

position at a given time, then, by multiplying your speed and the amount of

time you have been travelling, you can estimate how far you have come. If you

also know the direction in which you’re travelling, you know, approximately,

where you are or should be.

There are – obviously – major problems with

this. Firstly, you have to know the exact position from where you are starting

your initial readings. This is easy enough when one is starting from a fixed

point of reference like a port (or an airport). But if one then changes speed and/or course,

one or more times, one needs to know at what point one changed, and in what

direction, and factor that into one’s calculations.

Direction is not necessarily a problem if

one has working compasses. But if one makes a mistake in calculating one change

point, one’s further calculations will, however correct, still fail to show

one’s correct position. This is even truer if there is a strong wind blowing

across one’s path, because a strong wind can blow even a fairly large

aeroplane, like a B29, off course.

Over land this is not necessarily a

problem; mountains, rivers, cities and other prominent landmarks provide handy

reference points. For ships, too, this is not always a major hurdle, for there

are islands, lighthouses, coastal features like cliffs, and the like. But over

the ocean, especially when speed and course vary multiple times, it becomes

difficult (even with modern computerised systems) to calculate position, and

errors constantly creep in. These errors have to be corrected by some means.

The commonest way of doing so was by calculating one’s position with reference

to a star whose position was known (such as the North Star), or the sun whose

position at any given time over the horizon is known. But this is dependent on

one’s being able to see, and measure one’s position from, the stars or the sun.

If one is unable to do either, as Flying

Flimflam was in the heavy cloud, one has to rely on external navigational aids.

At the time the commonest such external aid was the radio beacon. This was a

radio beam relayed by signal stations, pointing the way across the land and

ocean towards one’s destination. Direction-finding equipment fitted on the

aircraft would locate this beam, and theoretically it would be easily followed

all the way to the target.

Of course, this depended on said direction

finding equipment working properly. And, seeing how far Flying Flimflam drifted

off course, it is obvious that, for some reason, its radio direction finding

equipment was malfunctioning.

The equipment had been functioning during

the test flight the previous day, however, quite perfectly, and on the trip

from California to Guam the day before that. What could have happened to cause

this malfunction?

O’Brien and Xavier claim that by far the

most likely reason was a massive discharge of static electricity while the

Flying Flimflam was passing through the centre of the storm. Basically, the

plane was struck by lightning.

Lightning strikes are far from unusual, of

course, and planes are regularly struck by them without major effects. But

unlike modern aircraft, the electronics of aeroplanes of the era – like the B29

– were not shielded against electric interference. A massive electrical

discharge may have left the plane apparently untouched, but damaged enough of

the wiring of the direction finding apparatus to seriously compromise its

ability to pick up radio beacons.

Even if one disregards the lightning strike

hypothesis, one is still faced with the fact that the Flying Flimflam wandered

off course by almost two hundred

kilometres. One can only explain this by a failure of navigation so extreme

that only one of three possibilities exist:

Either the navigator was incapacitated, or he was deliberately sabotaging the mission by leading it astray,

or his navigational equipment had

suffered a catastrophic failure.

There is no fourth explanation.

One need not (though O’Brien and Xavier do,

at some length) discuss the relative likelihood of these three possibilities.

Briefly, if the navigator was incapacitated, Finn could not have failed to know

it, and would have either aborted the mission or – since he and his co-pilot

were both trained in basic navigation – would have substituted for the

navigator. As for the possibility that van der Bedriegen was deliberately

sabotaging the mission, this was a handpicked man, like all the rest of the

crew, each of whom had been trained and indoctrinated for a mission like this.

We would have to believe that he would suddenly decide that he could not carry

out the attack he had prepared for his entire career, and then set out to try

to wreck it in a peculiarly pointless manner (since the Flying Flimflam reached

North Korea in any case). We would also have to believe that while he was

carrying out this sabotage, his fellow crewmen, including the pilots, the radar

operator (as shall be described), and the radio operator, failed to notice that

anything was wrong.

We would be expected to believe too much.

Only the third possibility – that there was

a major equipment failure – is, therefore, left. Whatever that failure was, its

effects are known: Flying Flimflam, instead of reaching the North Korean coast

at Point Zeke halfway between Singpo and Kimchaek, actually reached it just

under two hundred kilometres to the north east, not far south of Chongjin.

Even though the radio direction finder

might have been malfunctioning or totally inoperative, Flying Flimflam was not

helpless. It still had two other navigational tools at its disposal.

One was its VHF radio set, which could tune

in on radio broadcasts, such as those from Tokyo, and give a rough fix of the

direction in which the transmitter lay. But the clouds which still lay over

Honshu were filled with lightning, and disrupted radio reception. All the

Flying Flimflam might have been able to tell was that it was passing somewhere

in the vicinity of the Tokyo transmitter; it would not have been able to tell

more than that.

Once over the Sea of Japan, Flying Flimflam

could have homed in on radio broadcasts from Pyongyang. But, ironically, the

success of the “United Nations” forces had removed that possibility. When they

had been forced to abandon Pyongyang in the face of the Chinese advance, the

“UN” forces had largely destroyed the city’s infrastructure; and afterwards

they had been bombing it relentlessly. Pyongyang Radio, at this time, was

non-functional.

That left the other tool the B29 had, its

radar. Radar in 1951 was nowhere near as sophisticated as it is now; especially

in ground-mapping mode, it could just about tell land from water. But it was

good enough to be able to map the line of a coast, and provide an image which

could be compared to a large scale map.

And this, O’Brien and Xavier say, is almost certainly what van der Bedriegen

did. Why?

The reason is simple. On reaching radar

range of the North Korean coast – where the sky was still covered in thick

haze, with low cloud obscuring the ground – Flying Flimflam settled into a

holding pattern, waiting for the other planes to rendezvous. Since it was not

at Point Zeke, but nearly 200 kilometres north, it could not, obviously,

logically expect the other planes to join it there...unless it was convinced

that it was at Point Zeke.

Why would it be convinced of such a thing?

Well, the coastline just south of

Chongjin bears, on the radar screen, a strong similarity to that halfway

between Singpo and Kimchaek.

One can readily imagine what happened.

Finn, who knew he had flown over Japan and had reached the North Korean coast,

but not where, would have flown up and down along it, while van der Bedriegen

looked desperately for radar landmarks to find out where he was. With the sun

covered in haze and the land and sea below shrouded in cloud, one can imagine

his relief when the radar showed what looked like the correct point on the shoreline,

matching that opposite Point Zeke. Confirmation bias is a great motivator, and

with no other way of determining their position, both Finn and van der

Bedriegen would then be psychologically primed to insist that they were where

they needed to be, any niggling doubt to the contrary.

|

| Point Zeke, projected flight to Pyongyang and actual position of Flying Flimflam. Map from O'Brien/Xavier |

Therefore, certain he had reached Point

Zeke, Finn settled into a holding pattern, waiting for the other planes to join

up, as he was sure they would do at any moment. He was maintaining radio

silence, as he had himself ordered, and so were they, so they could not contact

each other by radio. And though time passed, and neither the other bombers nor

any of the F86 escorts arrived, the B29 did not break from its holding pattern.

What were Finn’s options at this point?

O’Brien and Xavier list these:

First, Finn could continue in his holding circuit until one of two things

happened: the sky cleared sufficiently to take a reading from the sun, which

could not have failed to reveal to van der Bedriegen that the Flying Flimflam

was far north-east of where it should be; or

until so much time had passed that it had become obvious that the other

planes would not make the rendezvous. At that point he could make one of two

choices:

Either he could continue on the mission alone, crossing the coast and

flying into North Korea. If he was unaware of his real position, he would fly along

the bearing which, had he been at Point Zeke, would have taken him to

Pyongyang. At the point where he was, though, he would have reached the Yellow

Sea – between the west coast of the Korean peninsula and the Chinese mainland –

before he realised his mistake. If he was

aware of his real position or became aware of it along the way, he could make

appropriate corrections and reach Pyongyang.

Or, he could abort the mission and turn back. If he did, he had two

further decisions to make:

The first

of these is where to make for: back to Guam, or to another USAF base, meaning

one closer to Korea. This gave him only one real choice: to land the plane in

Japan, probably Tokyo. Since Japan did not, publicly, permit nuclear weapons on

its territory, this would be a major problem, which Finn would be eager to

avoid; Japan would likely only feature in his thinking as a destination if he

had consumed so much fuel that it was impossible to return to Guam.

The second

was what to do with the Mark 4 nuclear bomb. He could either carry the

immensely expensive weapon back to Guam, or jettison it over North Korean

territory or over the sea. If he chose the latter option, he could try to

salvage something from the mission by arming it with the core and carrying out

a nuclear strike on any North Korean target of opportunity, no matter how

merely symbolic. Or he could drop it (either over North Korea or into the sea)

without the core, ridding the Flying Flimflam of almost five tons of weight and

making the return flight that much easier; to all intents and purposes, then,

Operation Rook would never have taken place.

Given Finn’s character, though, there was never

any doubt what choice he would make. His orders were to attack only in

conjunction with the other two planes, and his rigid adherence to orders –

which had commended him to MacArthur – did not permit him to carry on with the

mission on his own. He would wait as long as it took.

We shall leave Flying Flimflam to continue

flying round and round just off the coast in its holding pattern, and move on

to a very different plane, which was also in the air that day.

One of the most significant aircraft in

history was the little MiG15. The appearance of this jet over Korea in November

1950 marked the abrupt end of the almost unfettered dominance the “United

Nations” forces had enjoyed in the air. Flown secretly by Soviet pilots – a lot

of whom were veterans of WWII – and, increasingly, by hastily trained North

Korean and Chinese pilots, the MiG15 soon drove the older vintage “United

Nations” jets from the skies of North Korea. The only American plane able to

counter the MiG15, the F86 Sabre, fought the Soviet jet in furious battles over

“MiG Alley” in the north-west of the Korean peninsula; but over the eastern

fringes of North Korea, at this time the MiG ruled the skies alone.

Most of the MiG15 bases from which the

fighter challenged “United Nations” aircraft over North Korea were in Chinese

territory, in Manchuria. This kept them safe from attack on the ground by

“United Nations” aircraft, and also allowed them to take off and climb to a

height from which they could swoop down on American bombers and their fighter

escorts before crossing the border into North Korea. After attacking from

above, the MiGs would dive at top speed for the safety of the border before

turning to climb again.

One of the primary bases for the MiG15 at

this time was in Antung, across the Yalu river in Manchuria. On the 8th

April, a batch of freshly trained Chinese pilots had arrived at Antung, and one

of them was a young man called Wang Zhejian.

In April 1951, Wang Zhejian was 22 years

old. A native of Taiyuan in Shanxi, he had been an engineering student before

volunteering for the nascent People’s Liberation Army Air Force in 1950. As he

said later, it was mostly in order to get away from engineering, which he

neither enjoyed nor thought himself fitted for. Rather to his own surprise, he

was chosen for pilot training, and in the winter of 1950/51 was sent to the

Polnaya Chush training airport near Vladivostok, run by the 64th

Fighter Aviation Corps of the Soviet Air Forces.

According to Wang’s later account, he and the

other trainees were astonished at the food they received in training. At this

time the food given to the average PLA solder was basic in the extreme – a few

cups of rice and a cup of cabbage soup a day. On this diet, PLA trainees could

barely muster the strength to climb out of the cockpit after a training flight;

as a result, their Soviet trainers quickly switched them to a Russian diet with

large portions of meat[16]. Even with the better provender and

improved living standards, the exigencies of the war meant that the USSR had to

quickly produce large numbers of Chinese and North Korean pilots, so the

training was hurried as much as possible. By Wang’s own admission, by the time

he arrived at Antung from Polnaya Chush, he could fly straight and level, but not

much more than that; he was expected to “learn on the job” as wingman to a more

experienced pilot.

|

| Wang Zhejian in 1951. Photo from O'Brien/Xavier |

On the 9th – the day after he had arrived – Wang’s “on the job” training began. He was paired with a senior pilot, Zhang Liwei (at this time, the PLA had no formal rank system, which is why I am mentioning none; O’Brien and Xavier state that Zhang’s status would be equivalent to a senior sergeant, while Wang would be approximately an acting lance-corporal). There was, on the morning of the 9th, no radar warning of “United Nations” bomber forces approaching, so Zhang and Wang could go out on a routine patrol, which for Wang would double as a training flight. Wang was flying a MiG15 in contemporary “red tail” colour scheme (natural metal finish except for a red nose, tail, national insignia, and the aircraft number on the side of the nose) – in this case, aircraft number 3220.

|

| Modern photograph of a MiG15 in Red Tail colour scheme in flight. Note the three cannon under the nose air intake. |

This patrol was to proceed as follows:

After taking off from Antung, the two planes would fly due east, crossing into

North Korea over the Yalu. They would continue flying east, unless redirected

by their ground controller, until they sighted the Sea of Japan, at which point

they would turn back for home.

Soon after taking off at 11 am local time, however,

Zhang Liwei suffered engine trouble and had to return to Antung. Over the radio

he ordered Wang to keep to the original patrol, but to proceed north-east rather than due east to keep him away

from any possible enemy fighters (this course change was to direct Wang

straight towards Flying Flimflam; on

his original heading he would have passed to the south of the B29). Suddenly, high over North Korea, Wang found

himself alone.

Wang may have been inexperienced, but his

actions over the next hour show a remarkably cool head under what must have

been terrific pressure for a rookie on his first combat mission. At first he

flew uneventfully through clear skies, but as he passed Kanggye clouds began to

appear, as well as a high altitude haze. Although he was not, as he admitted

decades later, trained to fly on instruments alone, he carried on his initial

orders, flying on with the aid of his radio and gyro compasses, with one eye on

his fuel gauge and airspeed indicator as he desperately tried to mentally work

out how far he had come.

Just as he was about to give up and turn round,

Wang glimpsed, through a small break in the cloud, a stretch of coastline

ahead, and, beyond that, water. Although the break closed almost immediately,

he decided to fly closer, to be able to confirm that he had, indeed, reached

the coast. And just as he arrived over the area of the break, he saw, some

distance away and slightly above him, the silhouette of a large four-engine

aircraft.

It must be remembered that Wang had never

seen a B29 before. He had, however, encountered Soviet Tupolev 4 bombers on

several occasions during training at Polnaya Chush; and the Tu4, as mentioned

above, was a reverse engineered B29 and externally identical to the American

bomber. Knowing of this similarity, and unable to decide which plane this was, he

flew in for a closer look.

And it was then that the Flying Flimflam’s

tail gunner, Cretini, opened fire on him.

Xavier, who was to interview Wang decades

later, said that the Chinese pilot’s reaction was of astonishment. “I had done

nothing to him,” Wang said, “but all of a sudden his cannon shells were flying

around my wings. I could not even turn away without exposing my flank to him as

a perfect target. So, with no other alternative, I began to shoot back.”

Wang had three cannon under the nose of his

fighter: a 37 mm gun with 40 shells on the right and two 23 mm cannon with 80

shells each on the left. The cannon were relatively slow firing, with low

muzzle velocity, and the much greater weight of the 37mm shells meant they

travelled on a different trajectory from the 23mm shells. Because of all this,

against a small, fast moving enemy fighter the MiG15’s cannon were not always

effective. But against a heavy bomber – and the MiG15’s combat role had been

envisaged as a bomber destroyer, not an air superiority fighter – they were

incredibly fearsome weapons. As the bomber fell into the centre of Wang’s

reflector gunsight, he pressed both cannon buttons at once. Even through his

earphones he heard the hammering of the guns firing, and felt the vibration of

the recoil as the shells hurtled for their target.

Within seconds of Wang’s first burst, a

puff of black smoke spilled out from the (to him still unidentified) aircraft,

and it began to turn away in a shallow dive, heading out over the ocean,

fragments falling away from its wings and fuselage. Wang dived behind it,

firing burst after burst, until it disappeared into the cloud. Getting low on

fuel, and unwilling to risk crashing into the sea by diving into low cloud,

Wang turned for home.

What happened to the Flying Flimflam will

be discussed in due course; but we will first tell the rest of Wang’s story. He

made his way back successfully to Antung, reported his battle, and submitted

his gun camera footage as evidence. And he found his victory claim turned down

flat.

There were good reasons for this.

First, the People’s Liberation Army followed Soviet practice of the

period, which insisted that in order for an aerial victory claim to be

accepted, not only should gun camera footage show the target being destroyed in

the air or actually crashing, but wreckage be subsequently retrieved by

personnel on the ground[16]. Not only did Wang’s gun camera not show

the target crashing, it did not even show conclusively what kind of plane he

had attacked.

And that led directly to the second problem. Because Wang had not

come anywhere close enough to distinguish national insignia, for all anyone

knew, he might have attacked a Soviet Tu4, not a B29. In fact, the possibility

of a single B29 being off the north-eastern coast – not far from the Soviet

border – was considered so unlikely that Wang’s superiors assumed that it was probably

a Tu4. They in turn contacted the Soviet liaison officer to the air wing, Major

Artyom Duraleyev, and he, too, agreed that this was most likely the case. Since

nothing further was heard from the Soviet side over the next days, it was

assumed that the Russians were covering up this piece of fratricide as

assiduously as the Chinese were.

Success, as they say, has many fathers; even

perceived failure is an orphan.

What happened to Wang afterwards? Though he

flew through the rest of the war, he never made the grade of air ace (five

victories or more). He finally was

credited with two victories later in the war, and after leaving the PLA Air

Force returned to his engineering studies. At the time the book was written, he

was 89 years old, still in good health and full control of his faculties, and

living in Dalian.

Dalian is, of course, today not just a

major port, but one of the greatest hubs of Chinese innovation and technology.

It is also in North East China, squarely across the Yellow Sea from Korea; and,

therefore, in the zone slated for destruction by MacArthur, in the campaign of

nuclear attacks of which Operation Rook was to have been the first shot.

But, due to Wang Zhejian, Operation Rook

was over before it had begun.

10th

April: The Aftermath.

By 10th April the failure of the

attempt to nuke Pyongyang was manifest in MacArthur’s headquarters. Not only

had the Communist capital not been incinerated under a mushroom cloud, nobody

had the slightest idea of what had happened to the bomber. Hornswoggle Hannah

and Bluffmaster, struggling through the

same weather conditions, had finally arrived at Point Zeke, but there had been no

sign of Finn and his Flying Flimflam, which should have arrived before them.

Also, though the escort of F86 Sabres finally arrived, only eleven (of a

promised squadron of sixteen) managed to make contact. After waiting for ninety

minutes, Hornswoggle Hannah and Bluffmaster returned to Guam. Nobody heard

anything from Flying Flimflam ever again.

Since Finn could not possibly be in the air

any longer, he had either been shot down, or he had crashed into the sea. Since

the North Koreans or Chinese had made no statement about shooting down any

“United Nations” aircraft, it was assumed both by 9th Bombardment

Wing and MacArthur’s headquarters in Japan that he had crashed into the sea.

His crews’ families were informed that their loved ones were missing in an operational

accident, and that efforts were being made to locate and rescue them.

No such effort was made, and later the crew

were declared presumed dead. As Kurt Vonnegut would say, so it goes.

MacArthur was apparently informed of the

facts shortly after his morning conference; his reaction seems to have been to officially

pretend nothing had happened, and to try and arrange for a second attack on

Pyongyang as soon as possible. But someone

in his headquarters lost his nerve and – by late evening – contacted

Washington with the facts. Who this someone was is not known for certain; but

O’Brien and Xavier make no secret of their assumption that it was Humbug. After

all, Humbug was the only other person, apart from MacArthur himself, who was

privy to all the details of Operation Rook; and the authors point out that,

unlike MacArthur, Humbug never faced any consequences for his actions, and, in

fact, retired as a major general.

Jumping off a sinking ship can bring its

rewards.

Just when Truman received the news of