“I really don’t see,” said the science reporter, “why you don’t give

out the news to the world.”

The exobiologist raised a thick white

eyebrow. “Perhaps,” he said mildly, “it’s because you don’t have all the

facts.”

“The facts?” It was the reporter’s turn to

raise his eyebrows. “I’d have said the facts are clear enough, and momentous

enough, to share with the world. In fact, it will probably be the biggest news

since the dawn of the Space Age itself. The implications are staggering.”

“Yes,” the exobiologist agreed, drily. “Staggering is the word. You don’t know

just how staggering.”

The reporter glanced away from the

white-bearded scientist. Through the office window, he could see the distant

gantries and towering silver tanks of the spaceport. The tiny form of a

shuttlecraft crawled skywards atop a puff of pale yellow fire.

“Life elsewhere in the Universe?” he said,

still watching the shuttlecraft. “The rumours I’ve heard – very strong rumours,

from very reliable sources – say that

life’s been discovered not just on one planet, but on many. This means we’re so far from alone that we’re hardly more

than one of a multitude. So it’s natural to wonder why you aren’t giving out

the news to the public at large. Is it because of religion? Are you afraid of

offending the religious establishment?”

The exobiologist laughed. “If only our

problems were so trivial.” He leaned back in his chair and stared at the

reporter. “I take it that you decided to confirm the rumour before going

public? I mean, that’s why you asked for this interview, didn’t you?”

“Our magazine,” the reporter said stiffly,

“has never published anything on the basis of unverified rumours or innuendo.

That is not in our corporate ethos.”

“Really?” The scientist smiled sceptically.

“Anyway, the impression I got was that you were threatening to go public unless

we gave you an interview. That’s why you’re here now – because your magazine

was saying something tantamount to blackmail.”

The reporter didn’t say anything.

“We could have, of course, refused to say

anything,” the exobiologist continued, “and no doubt you’d have published some

completely garbled version. But we couldn’t take the risk of someone drawing

conclusions which might be even more alarming than the facts. After all, the

facts are bad enough.”

“How can they be so bad that they need to

be suppressed?” the reporter asked. “Things are so bad already that this kind

of news would be a beacon of hope. In the midst of war, climate change,

resurgent disease and creeping famine...” He stopped, embarrassed. “What I mean

to say is, anything that might show us hope would be an improvement, wouldn’t

it?”

“If it would be something that showed hope,

you might be correct.” The scientist shook his head. “But we aren’t convinced

that what we’ve discovered gives us any reason for hope. Quite the obverse,

actually. As I said, the facts are bad enough.”

“But you’re going to tell me the facts,

aren’t you?” the reporter asked. “You aren’t going to lie about them?”

“Lie?” The scientist laughed again, so

shortly that it was little more than a bark. “No, I can assure you that what

I’m going to tell you is the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.”

“And I can publish?” the reporter

persisted. “You won’t try to stop us from publishing? Because we’ll fight you if

you try to do that.”

“Oh, no,” the exobiologist replied, looking

slightly bored. “There’s no need for me to do that. After listening to what

I’ve got to say, I think you’ll agree that it’s better this news is kept from

the general public.”

That’s

for me to decide, the reporter thought, but looked

attentively at the white-bearded scientist. “Well?”

The older man pursed his lips in thought. “Your

sources,” he began, “are right in that we’ve discovered life elsewhere on other

planets. And it’s true that we’ve discovered life on many other planets – in

fact, almost every planet we’ve discovered that conceivably might have life has had life. But...”

“Yes?” the reporter prompted, when the pause

seemed to have lasted an inordinate length of time. “But?”

“But, we didn’t discover hundreds of

different types of life forms. Except for viruses and equivalents, we’ve found

only one.”

“One?” The reporter stared at the older

man. “I don’t understand.”

“Oh, you will,” the scientist responded

cheerfully. “You will.”

*****************************

The first

time we found them (the exobiologist said)

it was on a moon in the Giese system. At the time we didn’t realise what we’d

found, and even had trouble identifying them as alive. They looked more like

mineral formations than anything else – thousands of rust-red tubes, packed

side by side from horizon to horizon, their hollow ends pointing up at the sky.

It was only when the probes detected unmistakable signs of metabolism in the

tubes that we realised they were alive.

One of the probes cut away a sample for

analysis. Since we hadn’t anticipated something like this, the material had to

be examined by the fairly limited on board mini-laboratory, and it told us

little enough – just enough to confirm that it was part of a living organism,

and that it was primarily composed of fairly complex proteins. You know, like

all other life as we know it.

We were excited, of course. Very excited – it would be the first

life we’d encountered outside Earth, except for bacteria. Yes, we were excited,

but realised a lot more study needed to be done before we could even begin to

speculate on what they might be. We were still designing a probe tailored to

intensively studying them when we had another find.

This was on a high-gravity planet orbiting

the star they’ve named Diana the Huntress. It’s just about the opposite

direction to Giese, and nobody had anticipated finding life there at all. What

a planet that is, where the rocks are flattened from the pull of gravity, and

the atmosphere is a shell of gas thick as jelly. And yet even in that murky

brown wasteland, we found life.

It was a rough-crusted brownish slime,

coating the rocks and flowing sluggishly from place to place. For the brief

time the probe lasted, it watched patches of the slime crawl with agonising

slowness across the rocks, leaving cracked, crumbling stone in its wake. The

tentative conclusion we’ve made is that these slime patches leach the rock of

minerals in order to sustain themselves. We might have obtained a little more

information about them had the probe lasted longer.

What happened was that the slime ate the

probe. It was not mobile – under that gravity it would have been difficult to

have designed it to be – and its wealth of metals and composites must have made

it irresistible. The slime patches began gathering around it from almost the

instant of its landing, and they soon started to dissolve away the support struts.

The onboard computer was a fairly sophisticated model – it began sending back

signals which, had it been alive, we would have described as pain or distress.

We had to shut it down at the end, when it began to scream electronically.

But we did get a bit of information about

the slime before it ate the probe; the stuff was undoubtedly alive, and it was

composed of complex proteins.

Under the environmental conditions found in

that planet, you’ll understand, the presence of life was incredibly unlikely. We

could accept that it existed – after

all, we’d encountered it – but we couldn’t think of any way in which it might

have evolved on that planet, under those gravitational circumstances. But there

it was.

After a lot of brainstorming, we weren’t

any closer to arriving at an explanation. We began trying to design a probe of

materials the slime might not be able to dissolve away; the information we had

was so limited we actually knew almost nothing of the beasties’ actual

abilities. But before we could even arrive at a consensus on which materials to

try, another report came in from another planet – and then another, and

another.

Suddenly, like mushrooms springing up

overnight, life was being discovered everywhere. Sometimes it was on almost

airless worldlets, lichen-like films clinging to rocks and in crevices. In

other cases, we found immense leathery masses at the bottom of oceans of water,

reaching for the surface with tentacles tipped with knobs. And on other planets

we found the remains of life – planets so desolate that they were,

biologically, as extinct as the life they had once borne. We found fossils –

but we found more recent remains, desiccated corpses, skeletons, and the like.

We hardly had time to catalogue them all – they were so many of them, so many

worlds, that we never even suspected for a long time that there was something

very odd about them indeed.

One thing we did notice. These creatures –

wherever they were, whatever form they took – they were the dominant life form

on their worlds. They were so dominant, in fact, that in many cases there was

no other life at all, even when there should have been many others. And

sometimes they appeared in such circumstances that but for the fact of their

existence, one would never have believed those worlds might have had life. It

was very strange.

It was the genetic material that finally

tipped us off. Amazingly – considering the incredible variety of life forms

from all the different planets we were coming across – the basic genetic

material was the same. Even the

extinct forms – creatures so long extinct that we only found tiny fragments of

their bodies, a scale or tuft of hair, a frond or piece of tentacle – they all

had the same genetic basis. We

resisted the conclusion as long as we could, until certain observations meant

that we could resist it no longer. The various and completely different

creatures weren’t completely different after all – they were the same organism.

The rust-red tubes, the creeping brown slime, the blimp-like titans floating in

the atmosphere of gas giants – they were all the same.

And that could mean only one thing – that

there is something in this galaxy, a biological

force one might call it, that is spreading itself from planet to planet,

from system to system. We even found out how they did it. On a small moon in

one of the furthest systems our probes reached, there were great filamentous

growths of the things, which bore club-shaped pods at the ends of long,

delicate, hairlike stalks. At intervals these pods would explode, sending out

billions of spores at terrific velocity. Most of those tiny spores – about the

size of bacteria – fell back, but a fairly substantial number managed to make

their way out of the atmosphere.

And then we began to understand what was

happening. This biological force – whatever we choose to call it – its

imperative, its only goal, as it were, is to propagate itself. The spores we

saw would drift through space, and inevitably a few of them would find their

way to something – a planet or meteoroid, a comet or a piece of drifting junk.

And sooner or later one spore out of several billion would reach an environment

where it could survive – either directly, or by hitching a ride on a comet or

meteor which would crash on to a larger celestial body. If even one spore found

its way to a usable environment, that spore would start the whole process over

again.

Of course, the process is both extremely

slow and intensely wasteful, but there’s all the time in the universe to spare

– and the spores we collected are immensely tough, able to withstand vacuum and

cosmic radiation almost indefinitely.

And who is to say that the spores are the

only way to propagate from world to world? They can work in low gravity, but

there are other strategies – much more complicated strategies, but as effective

in the long term – that can be adopted to climb out of the gravity wells of

bigger worlds.

We haven’t even begun to scratch the

surface of all the adaptations that these creatures have made to themselves

over the aeons of galactic time. We do know that they are almost unimaginably

adaptable. They’ve managed to populate just about any environment that could

support life – and they’ve changed their physical form to fit that environment.

Their imperative to propagate impels them, and the immense plasticity of their

genetic code allows them to do just that. They are reproductive strategists

without parallel, and they could easily switch from one means to another if it

would suit their purpose.

And we realised one other thing. Any world

this biological force touches, it takes over completely. It sucks everything

out of that environment, leaving only a dry husk of a dead world. Water bodies

go dry, forests turn to barren wastes, all to fuel the onward march of this

biological force, its effort to evolve some means of propagating itself further

and further onward. Nothing matters

to it but its march across the galaxy. Nothing has been able to withstand its

progress, eating worlds and spitting out the remains.

Of course it will have had its failures –

but it will not have failed for want of trying. When one way leads to a blind

alley, it will try another, and another, until it succeeds or the stars burn

out. What it will never do, what it cannot

do, is give up.

And once the galaxy is conquered, its quest

will inevitably turn towards crossing the gulfs of intergalactic space – if it

hasn’t already.

After all, who knows how old it is, or how

long it has been since it started its blind journey of conquest? It could have

arisen in the first few billion years of the Universe. It could last as long as

space and time.

And there’s nothing we can do about it.

**************************

“Now,” said the exobiologist, “do you see why we chose to keep the

information from the public?”

“Less than ever,” the science reporter

responded. “Why don’t you understand – this is the perfect story to get the

people of the world to unite.”

“Is that so?” the scientist murmured. “You

really think so?”

“Of course I do,” the journalist said. “It’s

even better than I thought. Think of Earth as it is now, with nations and

peoples at each others’ throats, itching for an excuse for war, while ripping

the heart out of the planet. And think how they could be brought together

against this threat from outside, this alien force. We could call it the Eater

of Worlds, and show how petty human quarrels are compared to it. We could use

it rescue us from ourselves!”

“So you really don’t understand, do you?”

the exobiologist asked. “You haven’t thought this through to the logical

conclusion.”

“What conclusion?” the reporter frowned.

“What are you talking about?”

“You want to unite the peoples of the

world,” the scientist said. “You think it will bring them together – but

against what, precisely?”

“Why, against the threat of the arrival of

these spores,” the reporter said. “You told me yourself that this life force,

as you called it, consumes anything it touches. The only way we can save

ourselves from it is to unite, and make plans so we can successfully resist it

when it comes.”

The scientist smiled again. “What makes you

think,” he asked sweetly, “that it isn’t here already?”

The journalist stared. “Explain.”

“I thought I did,” the scientist said,

leaning forward, “I told you that this biological force would do anything to propagate itself, go to

virtually any lengths, even at the cost of destroying the world it inhabited. I

told you that it was infinitely adaptable, that it could fit itself to any

environment. Remember, too, that we found it in every direction we looked,

inhabiting every world it could possibly inhabit. And then think of what I told

you about the fact that high-gravity worlds require much more complicated

escape strategies than pods shooting spores into the upper atmosphere. Escape

strategies, one might say, which would require hundreds of millions of years to

come to fruition, and many, many, wrong turns and blind alleys. But, as I said,

the biological force has time.”

The reporter was silent.

“And think of Mars, that dead world right

next door, which once had flowing water and everything else that might have

fostered life, and has nothing now.”

The reporter was still silent. Gathering up

his voice recorder and notes, he rose to go.

“Just how do you think people will react,”

the exobiologist asked, “when they discover that they, and just about every

other living thing on this earth, are merely a means for a biological force to

spread itself across the galaxy? Their lives and loves, all of human culture,

religion, and interaction, their hopes and aspirations – all just a...a by-product of an ancient organism’s

efforts to reproduce. How do you think they’d react to that information?

“Also, don’t forget – it’s already succeeded. Humans have reached the

stars...

“Are you still planning to publish?” the

scientist called after the reporter, who was at the door. “Do you think the

world is ready for this news – or ever will be?”

The reporter looked back over his shoulder,

his face drained of all expression.

“Well?” persisted the exobiologist.

The reporter did not reply.

Copyright B Purkayastha 2012

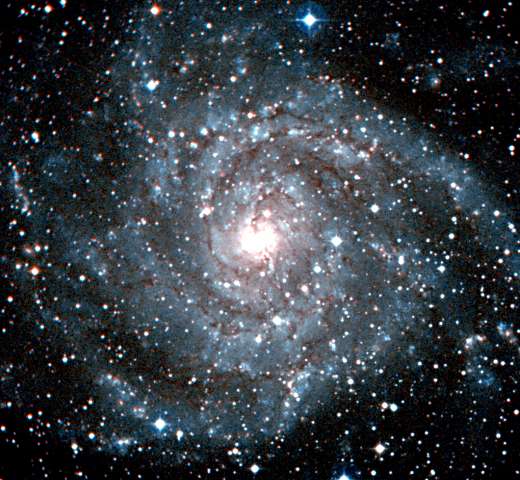

Well written Bill! Now I'm off, to read something that makes me feel a bit less like the slime we come from, and perhaps to look at the stars, with hunger....

ReplyDeleteI really like this one.

ReplyDeleteI mean, it's a little disturbing that it feels reasonable to assume it's accurate, actually.

And that might not be pure cynicism talking. Living things MIGHT be programmed to reproduce, expand to the limits of their environments, and then to keep reproducing and expanding.

Successful expansion would eventually mean that they'd reach the limits of their current environment's resources and then have to either go elsewhere or choke.

Despite all of the intellectual and spiritual dimensions we like to imagine we have, that initial imperative might be it.

Like Wallace said, slime.

Horny slime, but slime.